Dying Inside

By Robert Silverberg

I have not read any Silverberg and he is a giant of the science-fiction genre, so it is time I rectified that. I think Dying Inside was an excellent book to start with.

First published in 1972, Dying Inside concerns a man born with the ability to read people's minds. Imagine how great that would be? Well, not so fast! Set in mid-seventies New York, David Selig is now in his forties and has lived a decade or so with the realisation his powers are waning. This causes him much anxiety, to say the least, but the "gift" he was born with has been a blessing as well as a huge curse in his life. What might a life be like if you had this ability? Would you always want to know what people really thought of you?

Selig is not a particularly likeable man. He is cynical, unhappy with his station in life and full of guilt about his power. In fact, ignoring the telepathic ability, he exhibits many of the traits of the stereotypical New Yorker, and a Jewish one at that. I have not read much Roth, but perhaps he would be at home in a Roth novel. Or think of Woody Allen, minus the jokes, but plenty of black humour. Dying Inside is sometimes called "literary" science-fiction (descriptive terms like this can be fuzzy); in fact it is barely "science-fiction" at all. At least so far as most people would think science-fiction is (consider: Orwell's Nineteen Eight Four is science-fiction).

Perhaps "literary" because of this. Silverberg is a well read and erudite man and he has spent time polishing his prose here, inserting clever and thoughtful literary and philosophical references. He also conjures up the atmosphere of the New York of the times, especially the Seventies, post JFK and King assassinations, and the cultural, social and educational milieu (and dysfunction).

Not a long book, I found it quite a pleasure to read.

Good news everybody ...

I've been very angry about the Economist App performance this year, particularly how much it was crashing. I was having to do a factory reset on my tablet every 8 weeks to get a decent experience reading the magazine on my tablet. I am very pleased to say that things seem to have significantly improved however.

There was an update sometime in early November I think and since then it feels a little more responsive and also much more stable. So far, I have really noticed it behaving better. Now the ratings and comments I see on the Play Store are still quite bad but, for me, it seems like the update has fixed the biggest issues I had. I'm still cautious of course, but I am happy to report this. I should rate and comment about this on the "store" sometime soon as well.

This is the site of the former Royal Bank of Scotland building on Dundas Street in Edinburgh. A huge building, it was demolished recently and now sits empty beside King George V park. The development has hit a snag.

The original plans have changed and the developers are after new permissions from the council. The work is expected to include a lot of new student accomodation of the sort that has been put up throughout the city. Also a lot of rental, residential and a bit of office. There is a lot of pressure on housing: the amount available is insufficient and the costs are high and rising, but I have mixed feeling about this for a variety of reasons. Let's see what happens ...

More information is on the Spurtle.

There's a great article in The Atlantic called The Crumbling Foundation of America’s Military. It is a very sobering look at how far the war fighting capability of the USA has shrunk over the last thirty years. The war in Ukraine has put this into very sharp focus.

It turns out that a lot of America's industrial production of things like 155mm howitzer shells (see right) is via a process almost unchanged for a hundred years. Slow and expensive. The article notes that when Russia invaded Ukraine :

At that time, the U.S. was manufacturing about 14,000 shells a month. By 2023, the Ukrainians were firing as many as 8,000 shells a day. It has taken two years and billions of dollars for the U.S. to ramp up production to 40,000 shells a month—still well short of Ukraine’s needs.

There is a huge amount of dysfunction, inefficiency and cost involved throughout the supply chain. The USA is having to seriously consider a future conflict with a "peer" adversary, not armies like Iraq or the Taliban. They can produce technically advanced weaponry but at massive cost: the Houthi's launch drones that cost a few thousand dollars each. Tomahawks that are fired to intercept these are expensive :

When American ships began striking Houthi targets in Yemen in January, they fired more Tomahawks on the first day than were purchased in all of last year.

How inefficient and sclerotic is the industry? This was a painful read :

One of the most famous examples of this dynamic was an unmanned aircraft invented by the Israeli aerospace engineer Abe Karem originally called Albatross, then Amber, and finally the GNAT-750. He won a Pentagon contract in the 1980s to design something better than the drone prototype offered by Lockheed Martin, known as the Aquila. And he delivered, building a machine that cost far less, required just three operators instead of 30, and could stay aloft much longer than the Aquila could. Everyone was impressed. But his prototype vanished into the valley of death. Although it was a better drone, Aquila looked good enough, and Lockheed Martin was a familiar quantity. But Aquila didn’t work out. Neither did alternatives, including the Condor, from another of the Big Five, Boeing. Only after years of expensive trial and error was Karem’s idea resurrected. It became the Predator, the first hugely successful military drone. By then, Karem’s company had been absorbed into General Atomics—and Karem lost what would have been his biggest payday.

The Atlantic article is worth reading in its entirety.

It is a new and very dangerous world, much easier and cheaper to sow destruction and hard to defend against. The best thing we can all do is to avoid going to war, not at all costs, but certainly make extra effort not to. Wars have a habit of going in very different directions than the one we expect. I have just been listening to the brilliant podcast The Rest is History and their talks on the diplomatic failures that lead to the First World War. We need to learn from history and be much cleverer in how we deal with threats. We can't afford not to.

Greybeard

By Brian Aldiss

I was between books, picking new ones up wondering what to to go for, read the first few paragraphs of this and didn't want to stop. I liked the prose and seemed to be in just the right mood.

Greybeard is the story of people thrown together by circumstances and travelling down a river to the sea. Unfortunately, the "circumstances" are the end of the world, or at least the end of the human component to the world. A few decades ago, an "accident" has rendered humanity and some animals sterile : children have vanished and people are getting old. With the general collapse, nature is now rapidly reclaiming the world and what people survive exist in small isolated pockets, aging and some reverting to an existence informed by rumour, myth and fable. Forests reassert themselves and the nights are dark.

Greybeard is a melancholic story told in a beautifully lyrical style. Aldiss has a way with words in a sometimes spartan way. Great descriptions of the new natural world taking shape as Man diminishes; mist, water, oak and badger come into focus now. The characters, especially Algernon Timberlane ("Greybeard") and his wife Martha, come to life in a special way I think and their love is beautifully described. Martha has a great wit.

I hesitate to call the novel "gentle", it is a story of the end of the world after all and there is certainly some violence depicted. But this is not dwelt upon and no brutality. There is always a background possibility of danger of course. I've seen it described as "pastoral", and I think this fits and what makes the book so good. I've read three great novels from Aldiss now: Non-Stop, Hothouse and now this. I think Greybeard might be my favourite.

I am also reading Billion Year Spree by Brian Aldiss. This is his history of Science Fiction, first published in 1973 (the edition I have) and updated in 1986 (as "Trillion Year Spree"). Aldiss was also a very good reviewer, historian of literature and literary thinker. This history book covers Mary Shelley, Poe, to Wells and all the way up to the New Worlds era. Quite opinionated of course, and perhaps quite a few you might disagree with, but always interesting.

There is also another thing I started to notice about Aldiss' writing: his use of very unusual words sometimes. I have a fair vocabulary but do sometimes come across a word I've not seen before (I noticed this with a "literary" writer like A.S. Byatt or Iris Murdoch) but I've seen it a few times now with Aldiss. In Greybeard for instance, examples include: metoposcopy, tenebrific, tatterdemalion. Looking them up: divination through lines on a forehead, dark and gloomy (obviously from "tenebrae": shadows, darkness) and ragged or disreputable. I could infer tenebrific and tatterdemalion I think. Unusual words though.

The Time Machine

By H.G. Wells

I am embarrassed to say I have never read any H. G. Wells. I have rectified this recently however by reading his first novel, The Time Machine.

I should have done this years ago, perhaps as a teenager, because it was such a great book. I can understand why it was such a big success on publication in 1895: people were introduced to an author with a huge imagination and perhaps the first true science-fiction story. I enjoyed reading this immensely.

Not only an exciting adventure but thought provoking in a way that must have been quite unsettling to the readership back then. We not only travel to an almost unimaginably distant future of 802,701 AD but come to see what human evolution might mean; Darwin's theory being only a few decades old and still troubling to many. Wells was certainly not one to predict a heroic future progress of humanity. This might be one reason some critics and readers found him difficult. From Brian Aldiss' Billion Year Spree :

His audience is accustomed to powerful heroes with whom they can unthinkingly identify. A mass audience expects to be pandered to. Wells never pandered.

Perhaps a quote more applicable as his output increased, but a story where the human species can split into two, with one predating upon the other and all thought of science or art banished must have been hard to take. Even the idea of a deep "geological" time was fairly new (With Lyell's Principles of Geology published in 1830).

Wells' novel is brilliant. Now for The War of the Worlds I think.

The Kings of Eternity

By Eric Brown

Having read Eric Brown's Helix and loved it, I thought I'd read some more of his work.

The Kings of Eternity is a good science-fiction story that switches between the modern day and the 1930's. Three friends encounter an otherworldly portal that opens in the woods, and then an alien contact. This changes their lives, as you would expect, and over the years they have to come to terms with this and what it entails.

Brown manages to convey the protagonists well as men of the earlier 20th Century: their language and understanding of the situation is of that time. Luckily, the scientific advances at that point mean they have some sort of framework within which to place the strange events. The book is always very readable and engaging, even with a bit of a slow start. It is not an action packed story, although there is some action, but it gets into its stride quickly. What they encountered years ago endowed them with a gift and each has to come to terms with this. In fact, the novel is as much about relationships as "science" (or adventure), and in the end, a love story. So, a "scientific romance".

Well written and quite lyrical in parts, there is a lot to like about this book. In some ways, old fashioned (in an H.G. Wells way), but it is an uplifting and positive read.

It is that time of year again, and the Open Eye Gallery opens its 2024 Small Scale show.

Selected artists are invited to submit works in any medium, unframed, with the only restriction limiting the dimensions to 15 x 21 cm, the classic ‘postcard’ size.

Small pictures usually reasonably priced. Lots of good ones from good artists.

Below:

Left: Nestled off the Loch by Megan Burns, Acrylic on board, 15x21cm [link]

Right: Full Moon Afternoon by James Tweedie RGI, Acrylic on card, 15x21cm [link]

Below:

Left: Patience by Clare Mackie, Acrylic on canvas, 15x21cm [link].

Right: A Squirrel for Mary by Tracey Johnston, Acrylic on board. 15x21cm [link].

Most of the paintings are priced £200 to £600 but there are one or two priced much higher. I'm not sure why. Have a look and see what you think. The show is online only.

Across Realtime

By Vernor Vinge

This is the omnibus edition containing the novels "The Peace War" and "Marooned in Realtime".

Warning: perhaps minor spoilers.

The Peace War

What price would you pay for peace? What would it cost you? And what about costs to society? These are some of the things Vinge considers in his 1984 novel "The Peace War".

In the book, peace is imposed through a "Peace Authority", a world-wide government that has a monopoly on a powerful weapon: a weapon that can enforce and isolate threats, small or large. Through this, they keep society at a "safer", lower level of technological sophistication. The USA and other sovereign states do not exist anymore.

The weapon is a "bobble": an impenetrable force-field bubble around a space (and it turns out, a time). This can be used to completely isolate and neutralise a threat, whether people or missiles.

There is a resistance of course: a mix of clans, tribes, gangs and technology devotees Vinge called "tinkerers": or tinkers. The novel describes how the ungoverned and tinkers fight back against the "Peacers". Vinge is obvious about where his sympathies lie but he give the Peace Authority its due as well.

I thought this was a great adventure novel. Exciting and full of good extrapolations of the new technologies coming online in the 1990's and early 2000's.

Marooned in Realtime

In the sequel, Vinge shows us a consequence of having such "bobbling" capability. The story is sets millions of years in the future: because (in effect) these things act as a one-way time machine. This book is a murder mystery story and quite different to the first novel. I found it just as enjoyable though.

Vinge, who died earlier this year, had an abiding interest in and sympathy with the quest for knowledge and scientific progress. A Professor of Maths and Computer Science at San Diego State University in California, in many ways he epitomised the Californian techno-optimism of the 1980's and 1990's. The era of the early internet, the birth of the Electronic Freedom Foundation and magazines like Wired (founded 1991). I definitely sympathised with this vision, and still do, even though it can seem naive today and has been overtaken by the reality of the modern world (and everything this entails). We are less optimistic about technology today, sadly.

Science-fiction is a great genre for exploring all the different ways science and technology can change the world, and ourselves. I like Vinge's books: this is the second time I've read these novels. I liked them before and this time I think I liked them even more. If you're in the right mood for a book then it makes all the difference. I am sure I'll come back to them in the future again.

Chocky

By John Wyndham

John Wyndham's 1963 novella (it's a slight book) is about a twelve year old boy, Matthew, who has a friend he talks to: however, this conversation is only inside his head. The friend is called Chocky.

Not completely unusual in a child (the imaginary friend) but Chocky is unusual. Leaving aside the indeterminate sex (Matthew settles on "she"), Chocky asks some very strange questions, such as why are there two sexes? "She" also has some very odd views of the world. Matthew's parents become very concerned but are not sure what to do exactly. In situations like this, you can do a lot of harm trying to do the right thing.

This is a short read but a good one. The family (two parents and two children) are perfectly normal other than the fact of this strange unwanted interloper to Matthew's head. This is a long way from a story of a "demon" child or one of "possession" and it is all the better for that. Another worthwhile Wyndham read.

Above: Miss Candy Floss and Fun Lovin' Fifi (detail), Alice McMurrough, oil, 30x30cm

Do pet owners look like the pets they own? There are two paintings in this show by Alice McMurrough that would seem to point this way.

The show is an exhibition at the Open Eye Gallery (show now closed) of works by Alice McMurrough and Neil MacDonald, husband and wife. I've admired their work separately so it was great to see a roomful of the two side by side (they're married, something I didn't know).

Both are a bit surreal and dreamlike. McMurrough being more heavily infused with the surreal end of the dream spectrum. Quite odd with both human and human-like animals often taking part on her stage. Macdonald is a bit more restrained and paints the Scottish landscape, not necessarily using a straight-edge for buildings. I like both artists a lot. I am sure they both get tired of being described as "quirky".

Right: Moon Shadows, St Clemet's, Rodel, Neil Macdonald, oil, 38x44.cm

Right: Together as One, Alice McMurrough, oil, 30x30cm

The show closed on November 16th but you can see the paintings and read more at the gallery site.

Above: Copper Pan and Pears (detail) by Linda Alexander ROI, Oil, 28x40cm [link]

The Mall Galleries are hosting the 2024 exhibition of the Royal Institute of Oil Painters. A big selection of some great painting, big and small. I am always inspired by work I see here. If you can, a visit is best: you can't beat seeing a painting in real life. But online is good enough for me. I love big mixed shows like this.

Right: Coffee Followed by Beer by Rob Burton, oil, 23x17cm [link]

I like the "painterly" aspect to this. Really captures the dark and warm atmosphere.

Right: Unravelling by Felicity Starr, oil, 18x13cm [link]

Some beautiful works, some very small. This painting is a case in point and shows that even the most mundane subjects can be worth capturing in paint.

Many more pictures at the Mall Galleries web site.

A Room with a View

By E. M. Forster

E. M. Forster's 1908 novel is a completely different book to the last one I read. It is full of human emotion and human relationships.

Set in the early 1900's, Lucy Honeychurch is on holiday in Florence, chaperoned by her cousin Miss Barnett. They meet the Emersons, father and son, who give up their own rooms because they have a view, which the women had been promised. From there, it becomes a story of the boy's attraction to the girl and if this is reciprocated. It is a familiar enough story (girl meets boy etc.) but written well and told in a very witty way. There is plenty of good old-fashioned class based prejudice of course, but overcome in the end. Oddly, it is clear that tourism was a bit of an affliction even back in the 19th Century. Forster would be speechless at the sort of things that go on now.

Beautifully written and sharp, my one main fault would be with the older Mr Emerson's speech at the end to Lucy, explaining his son's predicament. It was a little too flowery and overwrought to be natural. Other than that, a book I thoroughly enjoyed. The Merchant/Ivory film adaptation is also supposed to be good.

The Voyage of the Space Beagle

By A. E. van Vogt

This book comes from the "Golden Age" of science-fiction - a period usually thought of as being the 1940's. The novel itself was published in 1950 but is composed of four stories published the previous decade (a so-called "fix-up" novel). Van Vogt is a new author to me.

The Voyage of the Space Beagle is considered a classic of the science-fiction genre and contains some of his first or earliest published work. It has had a significant influence on later science-fiction, especially films like Forbidden Planet and Alien, as well as TV series like Star Trek. The setting is a spaceship on a scientific survey mission, much like Darwin's original Beagle. It encounters some alien creatures, most of whom are hostile and dangerous. As well as some exciting action, the book explores the workings of science, in particular, Vogt's ideas of the compartmentalisation of the various scientific fields - his "nexialism" discipline aims to bring them together as a whole. The book also explores relations on board between the scientists and their leadership. There is a form of democracy on the ship but also a surprising amount of discord between some members of the scientific body.

This is a short read and one that contains plenty of action, even though some of it feels slightly dated. The "Discord in Scarlet" section includes a particularly horrifying and dangerous alien, one that could inspire some nightmares in a reader less inured to modern science-fiction horror (like Alien). It might be a little old-fashioned sometimes but this is mainly the way the men (there are only men on board!) interact and think: the civilian scientists have a somewhat military bearing as well. In some ways it is refreshing: direct and to the point. Like an older black and white film, men are in suits perhaps but the film is still great. I will read more van Vogt.

As a last word: it is not uncommon for people to believe that we're cleverer today, more intelligent and sophisticated than those that came before us. At least those before the twentieth century. But this is not true. People of the Middle Ages, for instance, certainly had less scientific or technological knowledge, but were no less intelligent. I had a slight prejudice against older science-fiction in the same way but realise now how wrong this is, having read a bit now and thought about it. It is a genre of ideas and the science or technology is just one aspect, and not necessarily an important one.

The Science Fiction Encyclopedia has an entry on the Golden Age of science-fiction. This is a great resource. Online only now but I was very lucky to find a paperback copy going cheaply in a charity shop a few months ago.

I visited the Burrell for the first time a few weeks ago. I've been meaning to visit for years.

The main reason to go was a look at the Degas exhibition before it closed. Being a huge admirer of the works of the great French artist, the exhibition was the big push I needed to get over there. I took the bus for a change, then a short (two stop) train journey from Glasgow Central (to Pollokshaws West), a short walk through the lovely park and arriving at the newly refurbished and fixed Collection building. It's been closed for a few years to have its roof fixed.

Above: One of the Burrell's display rooms.

Above: One of the Burrell's display rooms.

What can we say about Degas? He's usually classed as an "Impressionist", having exhibited in their exhibitions over the years (from 1874), but his work always differed substantially from the other artists so described (like Monet). He is famous for his portraits of people at work, whether ballet dancers or washer-women. An artist of the city and modern life. He did not paint en plein air as most of the Impressionists did (in fact, he was highly critical of the practice). The Burrell Collection shows how great a draftsman he was: drawings in pencil or pastel, a favourite medium.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

I had a look around the rest of the collection of course and it's impressive. A bit like a mini-Victoria and Albert museum, with a collection of furniture, tapestries, carpets, armour and ceramics: amongst many other things. I was lucky on the day, with the sunshine streaming through the windows and showing off some stained glass to good effect. I'll definitely visit again. With this and the Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow has some great attractions.

Helix

By Eric Brown

British author Eric Brown was new to me, until a brief mention on the Outlaw Bookseller's YouTube channel a while ago and then a recommendation by the owner of Transreal Fiction. His 2007 novel Helix was described as a good introduction.

Well, this was a great read: an exciting and action packed science-fiction adventure story.

A colony spaceship, a crash landing, almost immediate problems with hostile aliens and then a hard journey of discovery: not new ideas and nothing groundbreaking, but Brown tells the story so well, who cares? It starts well and stays good - and then mid-way through the book is a big surprise. An unexpected twist like this can really raise everything to another level. He creates believable and sympathetic characters (both the human and non-human) and we find we care about them. In addition,the book's lean and without the usual "fat" book bloat so many of the well-known science-fiction authors tend towards nowadays. A very refreshing and pacy novel that stands on its own (even though there is a sequel I will almost certainly read).

It is such a shame that Eric died in 2023.

I went to the Edinburgh Art Fair 2024 at the O2 Academy a couple of weeks ago. I've been for the past few years and went on a Friday to skip crowds at the weekend. It was certainly quiet, perhaps quieter than I expected.

The usual mix of good and mediocre ... and some bad. All a personal opinion of course: I go to this sort of thing because I love looking at art, particularly paintings. But I am always surprised (but shouldn't be by now) what sort of terrible stuff some people like. Then again, art can be all sorts of things to different people and many times it is just "home decoration" - like a mirror or a house plant. It's good if the sofa colour compliments the abstract painting. There's nothing wrong with that and, in fact, I occasionally paint something with a view to wanting a particular mood or atmosphere on my wall.

Kirsten Mirrey had a booth. I love her oil painting, seeing her work at the Abbeymount Studios open day a few months ago. Amongst many works, she had a very large (and just finished) oil painting up on the wall: a deer in the highlands. She seems to be doing very well (and that's not a surprise).

Right: Freedom. An oil painting by Kirsten Mirrey (from her web site).

The Day of the Triffids

By John Wyndham

A classic novel of science-fiction. The Day of the Triffids is a thoroughly enjoyable read: well written, exciting and thought provoking.

Many (perhaps most) people will be familiar with the story but they might have it a bit wrong, as I did. I've seen at least one film or TV adaptation a long time ago and had a slightly skewed idea of the book, which turns out to be more intelligent and much better. In fact, the cause of the "Triffid" invasion and the mass blindness is either different to what I thought, or more nuanced.

The tale of the end of civilisation is still chilling, even though there have been countless other books of a similar kind since. Wyndham does not dwell on the horror but is good at making us see how bad things are and what a bleak future could be unfolding. The horror or despair is secondary to the reaction of the people that survive and how they cope: from utter despair to a glimmer of hope, and back again. Part of the story is a search for someone lost, a search in the huge deserted land turning to desolation and wilderness, with the ever increasingly threat of the alien triffids. And, what of being on your own? Bill Mazen starts to realise that threats are not all external. Loneliness is something a sociable species is also prey to :

Something that lurked inimically all around, stretching the nerves and twanging them with alarms, never letting one forget that there was no one to help, no one to care. It showed one as an atom adrift in vastness, and it waited all the time its chance to frighten and frighten horribly - that was what loneliness was really trying to do: and that was what one must never let it do ...

It is easy to see why the book was a success. Maybe post-war Britain was in a gloomy mood and people were prepared to contemplate how fragile our world is. It still is. But rather than close with a despair, one can perhaps close with some hope that there are some that will rebuild. This was written in the 50's after all, and gloomier books came later. The Day of the Triffids is a marvelous novel that I expect will be read again.

Pavane

By Keith Roberts

Pavane is Keith Roberts' best known novel and considered a classic work of alternative history. The alternative historical stream makes this "science-fiction".

The book takes place in a Britain dominated by the Roman Catholic church and there has been no Protestant Reformation (it was crushed at birth). The cause of this was the fact that the Spanish Armada managed a landing in England and there was a Catholic uprising with Queen Elizabeth assassinated. What would today's Britain be like, hundreds of years after such events?

The suggestion here is: no industrial revolution, science and technology severely circumscribed, capitalism neutered, an entrenched social hierarchy and a mighty church (including an inquisition). Before the 19th Century, people did not expect the world to change much over time, if at all. "Progress" didn't happen and change was slow: but it can happen. People are still intelligent and inventive and some want freedom to explore and think new things.

Roberts' novel is set in the South West of England, primarily Dorset and surrounds. It is suffused with a rural, old-world flavour as you would expect but, more unexpectedly, harkening back to a more distant, possibly pre-Christian, past. He has an obvious love for this countryside and perhaps the old magic still lingers here. The episodic style gives us a flavour of the state of the world through the eyes of a steam-powered business entrepreneur, a boy being trained in the Signalling guild and a high-born woman chafing at the strictures imposed by a powerful Church. They are linked by family or setting. Times are changing.

The background is believable and quite British. The tale is a realistic exploration of this possible future: not quite the novel I expected but still fresh and interesting.

I bought a new keyboard and went with an HP 230 wireless model that includes a wireless mouse. It's inexpensive and only for use with in my living room, so not heavily used. I have not used it much yet but it seems fine so far. I would not want to use it for much "proper" typing though. The keys are "chiclet" style with little action.

There is always a "setup" sheet with this sort of thing: inserting the batteries, turning on mouse etc. It is always small with tiny text. Often not very useful.

But why can HP not also include a guide to what the keyboard "icons" mean? I'm familiar with many but some are a little mysterious. Technology "Icons" are supposed to make functionality clear.

I don't know what the "F1" icon means.

Or the "F2". Although F2 works as usual for "rename" in a file manager.

"F3" cut I assume. "F4" copy?

Anyway, it is such a small thing to document, why not do it? I could not find this information online.

I have been using a Logitech diNovoEdge keyboard in my lounge since 2009. It still works but has started to become a little unreliable sometimes and it loses connection for 5-10 seconds more and more often. It's been much used and I think it is a great keyboard for the lounge/TV. It is much better than any of the other wireless keyboard/trackpad keyboards I have tried: they are often poorly designed and also a low quality build. It is a real shame Logitech stopped making them years ago. Anyway, time to try something else.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

By Muriel Spark

Spark's novel is short, sharp, witty and ascerbic. She has a great ear for dialogue between the young schoolgirls under the spell of their charismatic teacher. A wonderful book.

Written in the late 1950's, it is set in the Edinburgh of the 1930's. World War One is still a presence but the effects of the depression has only a fleeting appearance in this more affluent world. Jean Brodie is a teacher at an Edinburgh girls school with a particular outlook on life. She is cultured, one could say snooty, loves High Art and looks down on science. Edinburgh is strait-laced and proper but there are some rough edges, as seen by the "Brodie Set" themselves during a walk through the Old Town. They come across a long line of men queuing in the street :

Monica Douglas whispered, "They are the Idle."

"In England they are called the Unemployed. They are waiting to get their dole from the labour bureau," said Miss

Brodie.

Jean Brodie takes holidays in Italy and admires Mussolini. She remarks that "In Italy the unemployment problem has been solved". How is left unsaid.

Children are very impressionable. Teachers are a big influence and in a position of trust. In modern parlance, they are "influencers". Today, of course, social media presents a much larger and more powerful array of "influencers", with pernicious effects sometimes. It's clear why parents have to care a lot about who you mix with as a child because their acquaintances have a bigger impact than you do. Like Jonathan Haidt, Professor of Ethical Leadership at NYU, we should be worried about the power of social media on children.

What I particularly liked about the book was Spark's dry and funny way with the children's dialogue. Sometimes silly, fantastical or funny. Occasionally, a little nasty (poor Mary MacGregor). She captures it beautifully.

"Miss Brodie says prime is best", Sandy said.

"Yes, but she never got married like our mothers and fathers."

"They don't have primes," said Sandy

"They have sexual intercourse," Jenny said.

The little girls paused, because this was still a stupendous thought, and one which they had only lately

lit upon; the very phrase and its meaning was new. It was quite unbelievable.

A very approachable and funny book, and still relevant today.

I have made a new web site to show art work I have created :

This is the first time I have done any "mobile" friendly web site work: mobile first. So I have also tried to familiarise myself with CSS features like flexbox layout etc. It has all been a learning experience. The Javascript "lightbox" is something I've taken from elsewhere (see below). I am now painfully aware of how unfriendly my main blog is to mobile and, at some point, I might have to try and fix this.

In the meantime, please check out the new site.

WARNING: The art site includes a "lightbox" (using lightbox2 but this does not work well on mobile devices. I may completely remove the lightbox, or try and replace with something else. More work needing done!

Non-Stop

By Brian Aldiss

To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive ...

R. L. Stevenson

Aldiss has this Stevenson quote front and center at the start of his first science-fiction novel: a short and pacy adventure published in 1958. By the end, you might also understand why.

The US title was "Starship", which gives some of the game away unfortunately.

Right: The cover of the old US hardback I have. Surprisingly, using the British "Non-Stop" title. The graphic design and artwork is, let us say, of its time. Publisher: Carroll & Graf 1989.

I enjoyed this book a lot: Aldiss has obviously thought through the sort of things that might happen if humans have to live on an interstellar spaceship for a very long time. Think of features of speech, custom, culture, religion and all manner of human relationships. We are a fractious people. Space travel is hard on us and our bodies.

The ship in use here would be called a "generation" ship today: a well used trope of science-fiction since this was written (Aldiss might have been the first to write about it properly). The galaxy is so big that the human brain cannot fully grasp the numbers involved; they are just so large. I am not sure we would survive such a journey, but if we did, it might end up something like this. I made some assumptions here and thought I had a good idea what the end would bring, but I was surprised and wrong. A good book, and shows you can pack a lot into less than two-hundred pages.

We are all dying, just at different speeds.

-- Thomas Crowwell in The Mirror and the Light.

The Mirror and the Light

By Hilary Mantel

We know how the story ends. Boleyn dies by the sword. Cromwell, the axe. Others die in very much worse ways as the authorities cut a swathe through the country. After some initial success, the Pilgrimage of Grace is bloodily suppressed by a vengeful King. Robert Aske, one of the leaders, was killed in a very cruel way. This episode features in H.F.M. Prescott's Man on a Donkey (a book I read a few years ago and thought good).

Cromwell keeps his own secret book about Henry where he writes down his thoughts and observations about the King in an attempt to understand him. In this final novel, Cromwell is much more introspective.

This last book did not disappoint me in any way. As a series, they are perhaps the best books I've read and have left a lasting legacy to me. I will return to them I'm sure.

The Mirror and the Light is the final volume in Mantel's Wolf Hall trilogy. I savoured the text all the more as I approached the final pages, waiting for the axe to fall and wondering how such an ending would be treated in the first person she uses. There has been some criticism (see wikipedia), mostly regarding the historical accuracy, but she's mostly had high praise. This is "fiction" we must remember but it is very hard not to find the world she creates entirely believable: the food, the smell, the weather and the people. I will almost certainly re-read the whole lot sometime, once again.

Mantel died in 2022. Thank goodness she lived to complete this.

And to finish :

Below: The original axe and block used during the execution of high-profile prisoners.

Photograph : By mwanasimba from La Réunion - Tower of London, CC BY-SA 2.0, link

From atlasobscura : This particular ax was last recorded as being used in 1747 for the execution of the Scottish Baron and Jacobite Lord Simon Fraser of Lovat, who, as a Highlander, fought against the Hanoverian forces during the battle of Culloden.

I came across a Publishing Weekly article about book sales recently. It appears that the types of books doing well, and keeping the sales numbers more respectable, are the so-called "Romantasy" books, a neologism that compresses "Romance" and "Fantasy". The cliché would be: romance books with magic included. I also see that Amazon have Romantasy colouring books but I hesitate to draw any conclusions from this.

Authors Sarah J. Maas and Rebecca Yarros are mentioned as being the current big sellers. I think I first heard the term "romantasy" from Stephen E Andrews on his YouTube channel Outlaw Bookseller and now can't help but see these books. His point was that the "Science Fiction" genre is shrinking and the "Fantasy" one grows, and it is all a matter of basic economics. Publishers go where the money is and their budgets are spent there. It's a shame that "science fiction" and "fantasy" are both dumped into the same bucket.

Maas certainly has a lot of momentum behind her, as you can see on the huge list of "midnight release parties" planned for her next book.

On the right: a photograph from her Instagram page of one of her book signings.

According to the article Boys Need Books by Myke Bartlett in The Critic, the publishing industry is majority female now: readers, authors, agents, editors, marketers. No doubt there are many factors at play here: possibly some over-correction of the previous male domination in years gone by. It's not a bad thing per se except how it might result in a different allocation of resources to the detriment of some market segments. A lot of the marketing is social media now of course: we have things like BookTube and BookTok (and I admit to liking a few YouTube "BookTube" channels). Maas has two million Instagram followers. Whatever she and other "Romantasy" authors are doing, it's working. But looking at the photo from her meetup above: where are the boys?

If boys don't read when young it might be difficult to start later. Maybe video games and screen time are an aspect of this but it's also possible that fewer books appeal to a boy nowadays. I'm sure publishers can do better.

On the left: Rebekah Greenway ("Booknuts") shows off her Midjourney and Photoshop skills in the service of Romantasy book characters. This is a picture from her Instagram page.

Midjouney? From their docs page :

Midjourney is an independent research lab exploring new mediums of thought and expanding the imaginative powers of the human species. We are a small self-funded team focused on design, human infrastructure, and AI.

So, there you are. You prompt the computer on what sort of picture you want and the "AI" will generate it and you then iterate on this (I assume). This is called generative AI. I wonder how many of these books are also written by an AI now? That seems a bit of a scary thought to me.

Molly Zero

By Keith Roberts

Score: 4/5

Molly Zero is a slim novel first published in 1980. Classified as "science-fiction", it is an adventure story set in the near future about a young runaway from "boarding school" and her escape to London from the North. Roberts is new to me but he has been much praised by Stephen E Andrews on his YouTube channel Outlaw Bookseller. Seeing the paperback in a second-hand shop at a reasonable price, I picked it up.

The future Britain here is much changed by some large catastrophe. The country is split into smaller units with names like Lothia, Cumbria and Wessex, each with a border but trading together. The economy is basic but technology exists, including aircraft, computers and hallmarks of a surveillance state. A government and police are ever present but in the background mostly; It is dystopian. Molly is a young girl brought up in (what appears to be) a boarding school, one of many called "Blocks". She wants to see the sea but the boy she runs away with wants to get to London and he gets his way. We follow their journey as they make their way, including a period with a Romany ("gypsy") travelling circus. There is a mystery about the source of the national damage, who is in charge, if there really are "elites" and where the young people in the Blocks fit. The novel speaks in Molly's voice throughout, the "second person present tense", an unusual choice but it works. As the tale progresses, Molly learns some hard truths about the world and how far some people will go to fight against the powers in charge.

The book is well written, short and pacy. The period spent in the circus with the Romany is very well observed and Roberts does well with the character of the young people and the society of the travellers they join. By all accounts, he was a difficult man to get on with and this seems to have negatively affected his written output (or at least the published part). I'll be reading Pavane sometime in the near future; a novel some consider his masterpiece.

Solaris

by Stanisław Lem

Score: 4/5

Solaris is generally considered one of the greatest science-fiction novels ever written. Stanisław Lem (1921-2006), a Polish writer, published the novel in 1961 while the country was under Soviet control.

The story concerns the arrival of a scientist to a research station that sits above a vast ocean covering the whole of the planet Solaris. It is quickly apparent that all is not well: an unexplained death as well as erratic and unusual behaviour from the remaining two scientists. Extremely odd things are happening.

The "ocean" of Solaris is very different to anything on Earth: a chemical soup, organic, inorganic, colloidal. It displays unusual behaviour (to say the least), including forming huge structures within itself; these sometimes stretch many miles and are of huge complexity. It seems to exhibit intelligence. Is it sentient? This vast alien environment is the center of a large research effort and body of "Solarist" literature.

When you're in the mood to read a book, you are much more likely to enjoy it; something I have become much more aware of in the past few years. Being short also helps. Solaris is well written and the translation seems good (in my Faber&Faber edition the translators are Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox) but there are some sections that are more difficult. These are lengthy extracts from "Solarist" scientific research literature and are often dry and can be dull. Although my eyes glazed over occasionally, these writings did expand on the strangeness of the planet. It is still an environment I found very difficult to visualise however. This is a "first contact" story but of a "sideways" kind: the fact that the contact is with something we just cannot understand at all is the core of the book. It is eerie, even creepy, and our many questions are never really answered. Much like the scientists, we have a lot of theories about the planet, but no real idea of what is going on.

The novel is a short, sharp exploration of what a true "alien" contact might be and also a look at how humanity sees itself as it ventures out exploring the cosmos. The novel's been filmed twice now. I've seen neither film but will try to watch them sometime.

I've been trying my hand at linocut printing, perhaps the easiest sort to do at home. I've been wanting to try printing for a long time. There's no need for a course of training or in-person instruction: just have a go. It's quite easy to get something on paper quickly (even if just basic shapes) and it is cheap to get going as well. YouTube is full of instructional videos.

Right: My fourth lino print, and my first done in more than one colour.

I've now done about five prints, including a couple in multiple colours, one of which you can see to the right.

The colour prints are created using the reduction method: the first (usually lightest) colour is rolled and printed, then you cut out a little more lino where you want to keep this colour. Then roll the next colour and print again. Things can go wrong ... but so far not in a ruinous way!

In the picture below you can see the three stages of the three colour print "owl2": firstly turquoise (right-most), then, going right to left, the second colour blue added and then black to complete. The lino block is shown above the prints alongside the cutting tool I used.

Like any creative endeavour, practice is what gets you better. Right now I'm back to an oil painting but linocut printing is great fun. The focus of carving the block feels a little like a form of meditation. Time passes quickly.

Above:Edinburgh North Bridge and Salisbury Crags, oil

I visited the City Art Centre at the weekend to see their exhibition Adam Bruce Thomson: The Quiet Path. Thomson is a little known Edinburgh artist of the 20th Century.

The "quiet path" is a reference to his unassuming nature and low profile. Thomson (1885-1976) was an Edinburgh born artist and spent almost his entire life in the city, including a long spell teaching at Edinburgh College of Art. The college was formed in its present state (and site) in 1907, and Thomson was a student himself in the early days.

The exhibition is over two floors and shows his flexibility in oil paint, drawing and print making. I was also particularly drawn to some great pastel pictures, colourful and bright.

Adam Bruce Thomson is much less known today than some of his more famous contemporaries and that is a shame. Hopefully this small exhibition raises his profile because he deserves a wider audience.

The exhibition runs at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh until Sunday October 6th 2024 and is free.

Above:The Road to Ben Cruachan, 1932, oil

Above:Trees and Cattle, Colvend, 1920's, pastel

Above:The Old Dean Bridge, 1932, oil

Piranesi

By Susanna Clarke

Score: 3/5

Susanna Clarke had quite a bit of success with her 2004 novel Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. I liked it, but it's a long book and I had to slog through some of it. You need to be in the right mood to immerse yourself in an alternate magic-suffused Victorian world, with a writing style to match.

Piranesi is her most recent novel, published in 2021. This is a much shorter book, less than 300 pages, but in a similar vein to Jonathan Strange: quite strange and fantastical. A man wanders around a large, many roomed mansion "house", multi-levelled, ramshackle in parts and containing hundreds of strange statues. Some statues on plinths and some seemingly bursting through the walls. With an occasional missing roof, the rain and low cloud might chill the air, and the sea can come crashing through the building. He seems to have a rough and mean form of existence but, child-like, he seems happy enough.

It is quite hallucinatory and odd; some form of larger picture emerges slowly from Clarke's careful interleaving of fragments the "Piranesi" character puts together over the course of time. This is not reality as we know it.

What I most like about Clarke's writing is her positioning of "magic" as being something that is far from the modern conception: a bit of a conjuring trick, superficial entertainment or illusion. Magic is a more primal aspect of the natural world and something to be very wary of indeed. It can be beautiful, perhaps wondrous but also awful and frightening. A "fairy" in this world (see Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell in particular) might be intelligent as well as completely malevolent. You don't want one to take a dislike to you. There are no fairies in Piranesi but there are dark undercurrents of hidden or forgotten knowledge; perhaps best left that way. Beguiling and strange, it was short enough to stay interesting until the end. An enjoyable distraction from the modern world.

The Dervish House

By Ian McDonald

Score: 5/5

It's sometimes the case that I read a book, want to review it but either never get round to it, or start a review and never finish it. For a book I enjoyed as much as The Dervish House by Ian McDonald, I really need to make that extra effort. This 2011 novel deserves high praise.

It is a little different from the start: the setting is a near future Istanbul, a city with a vast history and a multitude of stories. The novel has been classed as "sci-fi", even a form of "cyberpunk", but designations such as these, like so many genre pigeon-hole's, do it a disservice. Yes, there are some futuristic elements: advanced personal technology, nano-technology, AI. And we mustn't forget the shape-shifting robots! But it takes these elements and treats them the same way we treat our smart-phones, crypto-currency and AI chat-bots. They're part of the scenery, or a child's toy.

Whatever the genre, it's a thriller and adventure story. A nano startup chasing financial investment and also a missing "document" essential to this. A wheeler and dealer commodity trader trying to pull off a less than straight-up deal. A hunt for a mysterious historical artifact, perhaps only a legend. A bomb on a tram that might cause more than physical damage. A boy's dangerous game spying on people who have a monstrous plan. And an old man with a chance at getting back at a past tormentor and perhaps a reconciliation with a lost love. There is lots going on and many threads to keep our interest, with a small cast of believable, funny and colourful characters. I think I did laugh out loud at least once.

There's action, emotion and tension but what raises the book far above the average is the setting in the ancient city and our immersion in it, old meeting the new. A very good, well written novel and an author I will be sure to pick up again.

I've recently finished reading Paul Pope's graphic novel "100%". I thought it was excellent.

I hadn't heard of Pope or seen anything by him until I saw a video review of the first issue of his 1995 comic "THB" on the Cartoonist Kayfabe channel. The channel's been a source of some great material and I hope it manages to survive the recent terrible events.

THB is a very early Pope comic, self-published from the mid-1990's. As soon as the boys opened it up it was intriguing: different just looking at the title and graphic design. The first thing I noticed about the art was the fluidity of the ink style, quite obviously brush driven rather than pen. Using a brush for inking is much less common, even back before digital production took off.

"100%" dates from the early 2000's but, again, you can see the dynamic black and white brush-work and his recognisable style in full effect. There's an organic quality that I think only a brush can fully exhibit. There is a "Paul Pope" face and figure style.

On top of the great comic art, the actual story itself is good. The story is an aspect of a comic that is often less developed, if not sometimes puerile (with some notable exceptions of course). Adults need something better and "100%" is that, just don't expect superheroes or explosions. From what I can see, Pope does pretty well selling original art as well. Definitely someone worth reading.

I saw Hawkwind live in concert last weekend. I haven't seen them live in years: decades in fact. Dave Brock is the cornerstone of the band of course and the last remaining original. He might be creaking a bit, but at 82 you have to give him huge respect for keeping things going and doing his bit for psychedelic space-rock. He looked good and played well: I hope I'm as fit as he is when I reach that age.

"Spirit of the Age" from the album Quark, Strangeness and Charm, stood out for me. I don't think I've ever heard it live before. That was a great album and definitely hugely enhanced by Robert Calvert's song writing. Great to hear it live.

I missed out on their last concert up here (their 50th anniversary tour) and was kicking myself for not going. Not even Hawkwind can go on forever but, luckily for me, they don't know when to stop touring. And good luck to them.

I have factory reset my tablet again yesterday (April 8th). The Economist app has started crashing too much again. How much? It crashed 4-5 times while I was trying to read an article at lunchtime: I'd restart the app (with all the delays that involves), go back into the article (more delay) and then maybe get 10 secs and then a crash again. Repeat. I gave up that article. As I detailed before, I'm back in the same hole.

My last factory reset was back in February 2024 :

2024-02-07 --- factory reset .. 2024-03-09 --- crash 2024-03-13 --- crash - then crashes on 16,25,27 2024-03-29 --- x2 crash - then once each day .. 2024-04-06 --- x3 2024-04-07 --- x4 2024-04-08 --- x5+

So it looks like I get about 4 weeks of decent behaviour but then a slowly degrading experience for the next few weeks. I'll see how this reset goes. Would I carry on paying for this? Maybe, assuming the discount I got. But it is wearing thin. I'll have to decide in September.

Like many people, I was shocked earlier in the week to read about the accusations against Ed Piskor, comic book creator and half of the Cartoonist Kayfabe YouTube channel. But it was just terrible to see that he then killed himself two days later. Just absolutely appalling. I am still trying to process it. Ed and his channel co-host Jim Rugg have been constant companions to me over the last few years: I've watched and listened to the channel very regularly, particularly when I paint. They started as pandemic lockdown companions. Ed loved comics: their creation, the artistic process, techniques involved, the business, the history, everything. An infectious enthusiasm.

I have to say that my heart goes out to his family first and foremost. Also to Jim Rugg, the other half of the channel, who must be devastated over the turn of events this week. What a tragedy this has been. I'll miss Ed a lot.

The Lambiek folks have an overview of his life, work and death. Also, the Comics Journal.

What a terrible week.

Hyperion / The Fall of Hyperion

Endymion / The Rise of Endymion

By Dan Simmons

Score: 5/5

Good Friday was a very apt time to finish reading the Hyperion/Endymion novels by Dan Simmons. There are clear parallels to Easter here that become very apparent as Endymion reaches its climax. Like the biblical story, the culmination of Rise of Endymion is horrifying and absolutely devastating.

These are long books (I read the four novels in the two volume omnibus editions): each book approaches or surpasses 400 pages, so there is a significant investment needed to read these. Following the characters over so many pages means you develop a relationship with them, perhaps love. As I reached the end, I felt a strong emotional response, even choking up to a degree. Great stories can have this effect. A very good book.

The Hyperion series is much more than a "space opera", although it spans the galaxy. As Aenea says to Raul at some point: Love is the Prime Mover of the universe. The gospel she "preaches" is one of non-violence and the core of the book is actually humanity, even humanism, but nothing supernatural. So, more than a space travel action-adventure but there is fast paced and bloody action, tremendous violence, demon-like non-human entities, "AI" and "time travel". There is something for everyone if you are in the right frame of mind. Wait until you are and you will not be disappointed.

I considered reducing the score and penalising for the length of the books (i.e. rating a 4/5). I think they are a little too long in fact. However, the final account makes up for this in my mind and deserve top marks. I do not mean to imply 5/5 makes them perfect.

Now for some more Japanese culture, this time animation, also known as anime.

The most famous Japanese anime studio is Studio Ghibli, a company I've come across many times but never seen any of their films. A lot of people really love the stuff they make. As I've said, I've never had much interest in manga, or anime, but I've been been intrigued enough now that I decided I should should watch one. I recently saw Spirited Away, one of their most popular productions (and also a 2003 Oscar winner).

It's a simple story about a young girl separated from her parents and trapped in a ghostly world of spirits, complete with magical people, weird entities and strange creatures. The world appears centered on a large bath-house run by a witch and the little girl has to find a job and work out how to escape and save her family.

Well, I really loved the film, enjoying it immensely. Charming and beautifully made "cell" animation, I can see why the the Ghibli "style" is such a worldwide success. There's a bit of a "signature" style, a traditional animation look alongside atmospheric painted backgrounds. I can understand a film like this being a big hit for both children and adults. Funny moments but also themes that tug at the core human emotions of love, loneliness and loyalty. It's also a refreshing change to see a film informed by Japanese cultural traditions even though it speaks to universal traits.

A film easy for me to recommend wholeheartedly. I will try and watch another Studio Ghibli production.

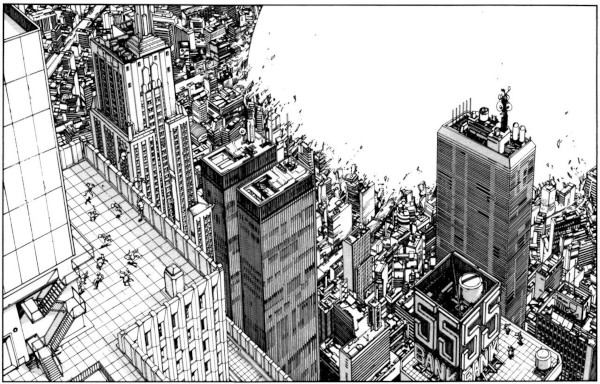

I finished reading Akira a couple of weeks ago, getting through the last of the six volumes. A very impressive work and I thoroughly enjoyed it. As I mentioned recently, there's never a dull moment, the story moves quickly, there's a lot of action and, of course, the art work is exceptional. What surprised me somewhat was the writing: it was much better than I expected and not in the least "childish", even if it has to be a little basic at times. A comic strip is a lot more than just the drawing, even though that is always the most visceral and accessible aspect of the work. This was easy to read and had a satisfying and moving conclusion. I completely understand its classic status.

Katsuhiro Otomo's art is detailed and dynamic. He really puts Neo-Tokyo and its inhabitants through the wringer with great drawings of buildings, destruction, military hardware, motorbikes, guns. Did I mention destruction? Masterful stuff. The one small criticism I have it that sometimes it was a little hard to see what happening in a panel there was so much detail. But this is a work worth paying attention to.

A wonderful book that I'm glad to have finally read. Perhaps I'm of an age that I really appreciate the whole package now but I would recommend it to any age group, teenage and up.

I am yet to see the animé film, but I am told it is good. Something to look forward to.

I recently wrote about my poor experience with The Economist android app. Well, since a factory reset, I'm happy that things have improved immensely. It is still somewhat slow and unresponsive, but the main problem I had was the crashing, and this has (mostly) stopped.

I did the reset on February 7th. I got my first app crash on March 9th, so got about four weeks of relatively pain free reading. Since then, I've had two crashes in the past week, so possibly a sign things are degrading a bit again. The app is still a bit slow and annoying sometimes but at least I now get a chance to read the articles. And this makes a huge difference. I'll see how it goes over the next week or so. This level of performance is just about "good enough" for me.

Above: library problems. Photo: Christine Ro (via BBC web site)

I recently wrote about ransomware and paid some attention to the British Library's current problem with this scourge. Well, a BBC article (Why some cyber-attacks hit harder than others) returns to the scene and covers the continuing issues and costs being borne. It's a sorry state of affairs. Looks like people are having to order books with paper forms and the digital media is still offline.

The Russian hacker group Rhysida claimed responsibility, and demanded a ransom of 20 bitcoin (equivalent to £600,000 at the time). After the British Library refused to pay up, and following an online auction of stolen data, the hackers leaked the nearly 600 GB of private information on the dark web.

Of course, Russia. The country has long been a center of criminal "hacking", state sponsored and private enterprise. Russian authorities look the other way as long as these groups don't attack Russia itself; maybe the state will co-opt or sponsor the activity. China is another major offender. The New York Times via the archive site:

Leaked Files Show the Secret World of China’s Hackers for Hire

The Chinese government’s use of private contractors to hack on its behalf borrows from the tactics of Iran and Russia, which for years have turned to nongovernmental entities to go after commercial and official targets. Although the scattershot approach to state espionage can be more effective, it has also proved harder to control. Some Chinese contractors have used malware to extort ransoms from private companies, even while working for China’s spy agency.

The problem we have is that computer and network security is hard. As well as the actual "technical" mitigations we can use (e.g. spam filters, firewalls), people themselves are usually a weak link. Anyone can be misdirected or scammed, even "experts". And almost everything is connected to the internet today, including everything that keeps civilisation actually "civilised" and people alive. Let's hope things don't get worse. And to be clear, I don't think ransoms should be paid because it just encourages these attacks.

Above: Akira - The bomb

Above: Comiket Tokyo, a huge Japanese comic fair held

multiple times a year.

Comics are still a big industry and the largest in the world is in Japan, followed by France and the USA. Japan has a long history with comics (Manga) and the market there is huge with lots of physical comic books sold and massive Manga shows. I've been watching the Cartoonist Kayfabe YouTube channel and my eyes have been opened to just how big comics are over there.

France is the second largest market for comic books (called "Bande Dessinée" or "BD"). The Guardian have a decent article online about the large comic convention held in Angoulême, France, every year:

France’s comic-book tradition is hitting new heights.

Left: At the Angoulême comics fair. Photo credit: Yohan Bonnet/AFP/Getty Images in The Guardian

Like the Japanese, the French do comics differently to us in the UK. Whereas the UK public has mostly seen "comics" as a form of entertainment for children, the French have seen comics as an art form and, as such, given them much more respect. The gap in perception has narrowed over the past two decades but I suspect it is still there. When I first looked at French comics the difference in the culture was like night and day. In the 1980's I started to read BD by the likes of Moebius, Bilal and Druillet: the French magazine Métal Hurlant was seminal at this time (and its American cousin Heavy Metal). Manga has made big inroads to the French market over the past few years: over half the market according to The Guardian article.

Right: Métal Hurlant no.8. Cover (detail) by Jean-Michel Nicollet.

With manga, I certainly looked at it back in the day (mid-80's) but I think this was just before of the good sort was available.

I just couldn't get past the way faces and eyes were drawn, or the often childish looking characters. Looking back now, I know I jumped to

entirely wrong conclusions, but with so many other great comics coming online to me at the time, I never found time to take another

look.

One of the best known Japanese comics, and perhaps the biggest hit of them all, is Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira, first published in Japan in 1982 with a first edition in English (Marvel's Epic line) in 1988. To many, this was the book that completely changed their perception of manga.

I might have glanced at Akira years ago but it would have been a superficial look. The guys on the Kayfabe channel are massive fans of Otomo and have been going through his comics and paying serious and deserved attention to their quality. It's been enough to have me taking a proper look. I've been lucky that my library (Edinburgh Central) has a fairly decent selection of comics and graphics novels so, when I saw they had the first few Akira volumes on the shelf, I knew what I had to do.

I've now read volumes one and two, and have three and four out on loan to read. Each is a thick black and white book but not heavy going in any way and the story moves along briskly. It's set in a near future "Neo-Tokyo", rebuilt a few decades after a World War and after massive devastation caused by a "new type" of bomb dropped at its center (see top image). A cyber-punk type future we've seen a lot more of now but here is a well paced story, fresh and well written, with great art. Otomo excels at detailed buildings and backgrounds, machines and action.

The comic reads surprisingly well and looks beautiful too: I am ashamed I took so long to pick it up but would recommend it to anyone.

Below: A panel from Akira. © Katsuhiro Otomo.

My tablet has taken to telling me something I am painfully aware of. The Economist android app crashes. A lot. In fact, it crashed over ten times for me at lunchtime yesterday. Given that it is also very slow, it takes a long time to start it up and get to a point I can attempt to read something again (it also loses the current article). It might crash again before I even get to the article again, if I can find it (it sometimes rearranges the home page and hides stuff). This is the way it is every day now.

I like The Economist magazine in general and have been a subscriber for many years now. I still find the writing good and explanations of current affairs and business excellent, even if I am a bit less aligned with it on some issues than I used to be. However, given the problems reading it, I will not extend my subscription again later this year.

I am also far from the only one having a problem. If you head over to the Google Play Store and look up the Economist App, you will see many people saying very similar things. This needs to be addressed or people will stop buying it. Fundamentally, what do we have here? A collection of text and images on pages wrapped in a "magazine". How hard is this? It is a solved problem.

I read on a Samsung Galaxy Tab A, from 2018. It has 3 GB RAM and 32GB storage. I use it only for the Economist app now. I see no reason why the Economist app should not work on this. If they really need to stretch the limits of what this tablet supports (but why?), give us a "lite" version. I refuse to buy another tablet just to read a "magazine".

I have tried a factory reset of the tablet. Things improved for a few days but started getting bad again soon after.

Here are some of the things wrong :

- The app is very slow and often unresponsive.

It is hard to tell if you've "clicked" the link and have to retry a lot. Finally, after a 10 second wait, maybe it will work. - The app crashes a lot (see above).

- The app "resets" itself to the home screen.

It rarely remembers your place in an article so you have to find it yourself, which is slow. - The downloaded issue has the same problems.

I've stopped trying to go through the "weekly" edition because it is even slower to get into. Even having supposedly "downloaded" it, you would not know. Everything behaves the same and a constant appearance of needing to download or refresh content. It's not just the ads.

- The "weekly" page usually shows me the wrong (previous) week. Selecting "Browse Editions" might refresh (slowly) and show all the available editions but does not let me select the new edition: it shows me the previous one again.

So, I have just about had enough. My subscription is good until the autumn but I will not pay money again for this horrible, frustrating experience. I will call their help center and let them know. I'd like my money back.

An Update

I've just done another factory reset, reinstalled the app from thePlay Store and logged in. I used it at lunchtime and, although the app was a bit slow and unresponsive to "clicks", it behaved better. It didn't crash once, which is the most important thing to me. I actually managed to read a few articles and not feel angry or frustrated at the end of my lunchtime. I'll see how it goes for the next few days.

The British Library has had a big problem recently, as they were saying throughout their web site :

We're continuing to experience a major technology outage as a result of a cyber-attack. Our buildings are open as usual, however, the outage is still affecting our website, online systems and services, as well as some onsite services. This is a temporary website, with limited content outlining the services that are currently available, as well as what's on at the Library.

This has been the case for weeks although it appears they are restoring some services now.

I've been reading about "ransom ware" cyber-attacks for a few years now: this is when an attacker gets access to a computer system, server or network and encrypts (scrambles) the files and data so the systems are unusable. They then demand money to unlock the data. Perhaps money not to leak the data online in public. This sort of attack has affected hospitals, businesses and government. It's getting worse. So bad in fact, that people are waking up to the National Security implications.

The Economist had a recent article about the problem (How ransomware could cripple countries, not just companies) and one of the things it mentioned was the fact that Bitcoin, a hard to track anonymous digital currency, is one of the things that made the problem much worse. In fact, Bitcoin is a major enabler of the crime :

The hardest part of a ransomware attack was once cashing out and laundering the ransom. Attackers would have to buy high-end goods using stolen banking credentials and sell them on the black market in Russia, losing perhaps 60-70% of the profit along the way. Cryptocurrency has enabled them to cash out immediately with little risk.

With everything increasingly connected (think "5G"), and network and computer security so poor (for many reasons), it might get very bumpy. Let's not talk about war.

Last week I came across yet another media report of ransonware : infecting a Bosch Torque wrench ("Handheld Nutrunner NXA015S-B 3-15NM"). This was detailed in a post on ArsTechnica.

My initial reaction was a bit of amusement: an internet connected wrench? But maybe a modern manufacturing business has a good case for logging or setting all sorts of things over a network: this was even part of the case for "5G" networks. But if so much of modern life is now network connected, how screwed will we be if it is attacked, compromised and rendered unusable?