Against a Dark Background

By Iain M. Banks

Score: 3/5

A Banks science-fiction novel but not set in the Culture universe. An aristocrat and her team of ex-military adventurers chase a mysterious book that leads to an even more mysterious, and almost mythical, "Lazy Gun" (the last of eight). Not as stupid as it might sound when laid out like that because being Iain M. Banks it still has much style and some substance. Even if it is not one of his best in my opinion.

Basically a fairly fast paced quest, with action and explosions a-plenty, and a lot of to-and-fro team bonding and banter. Some of it is very good, and there are also good set piece fights and other situations, but the whole never quite gels for me. The ending, even as action packed as it was, disappointed and was somewhat expected. In many ways, the lead character is set up to be extremely unsympathetic: an aristocrat capable of cold and off-hand cruelty. But Banks pushes you to root for her and her gang, and she is written much more sympathetically later on. If you know Banks' politics and worldview, this is slightly odd perhaps.

An accessible Banks book then, but not one of his best or most interesting.

I read a Charles Stross novel a while ago called Glasshouse. Set in the future, a passage in the book stayed with me. Looking back at the historical record and how much information has been stored, saved or lost, he described how a switch to digital storage had caused a big hole in the record because at some point, "for no obvious reason" everything had started to be encrypted. And that's what I thought: for no obvious reason. Why bother encrypting these blog posts?

For the last year or two, a big push has been made by some tech companies, concerned about privacy mainly, to move to securing and encrypting web sites: this uses the HTTPS protocol rather than plain unencrypted HTTP. Google have even gone as far as saying they would favour HTTPS sites over HTTP only, and start pushing in other ways as well.

This web site does not "need" encryption and contains no private or sensitive information, and for this reason I've held back and wondered what all the fuss is about. However, implementing the tech is now a lot less hassle than it used to be, particularly using something like Let's Encrypt, and I've now gone ahead and done it.

Now, when browsing the Sherringham Blog you can rest easy that the little green lock icon means it is much harder for anyone to intercept and change the web pages as they flow to your web browser over the internet.

I often use Teamviewer to remotely login and help relatives with various computer problems. It's a very useful application and I'm very grateful that they make it free for home use. Highly recommended.

Just before Christmas, it stopped working for one of my relatives. No ID shown, and it reported a problem connecting to its servers. After a lot of to and fro (it's hard doing technical support to someone who only has basic computer usage skills), I got Skype screen sharing going, which helped. I can't interact with the desktop but I could see what was happening at least and advise. Still, this all takes a lot of time. Errors accessing the Teamviewer web site (SSL secure connection issue?) made me worry about a virus or malware.

Eventually, a horrible thought dawned on me: Talk Talk might be blocking Teamviewer. I recalled they had done this before and there was an out cry from their users. And it turned out that this was the problem. Talk Talk, worried about internet scammers, have blocked Teamviewer. I found news and some details on The Register, then visited the Talk Talk forums to see all the people affected asking for help. Terrible again. It looks like a DNS block, so I talked my relative into changing to Google's DNS servers (helped by Skype) and got Teamviewer working again. Thanks Talk Talk for wasting hours of my time at Christmas!

Once again, I am just shocked that the company can do this without warning and mess so many customers around. A lot of these customers don't know what's wrong or how to fix, how to "chat online" with support, or call support and hold for help. It's just terrible. I've moaned about them before and, once again, would never suggest people use this company.

The Spy who Came in from the Cold

By John le Carré

Score: 5/5

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was le Carré's breakthrough novel of 1963, the one that made his name. When written, the Cold War had well and truly hardened into a very unforgiving and brutal form, albeit one that never got to the point of hot war between the major blocs. The Second World War and its aftermath was a fresh memory and the cynicism that a large number of the population of America and Europe subscribe to today had not yet manifested itself. So a book like this, an unsettlingly harsh look at the reality of the spy "game", was bound to cause a stir. Far from a James Bond world, we have troubling moral equivalence between the methods sometimes used by both sides.

A strong plot and great characterisation is the core of the book. Alec Leamas, the jaded British spy trying to do a last job and destroy his East German nemesis, is beautifully put together, as are his foils, such as the Jewish communist interrogator Leamas learns to somewhat admire. There's a horrible sinking feeling in the pit of your stomach as you know the way the final scene will go. But twists and turns are still to come, even if the sinking feeling never goes away, and there's a final emptiness at the end. A really great novel.

Rubicon

By Tom Holland

Score: 5/5

The late Roman Republic had no shortage of great people and large talents, a usually constant competition to amass the most money and prestige, elbowing out the competition, and in some cases, getting them exiled (or killed). This period of ancient history has held a fascination for a lot of writers and historians over the years and it is easy to see why. The personalities and exploits are often so outrageous that it is quite amazing that they happened over the course of barely fifty years. In a good writer's hands, these stories are still exciting, and sometimes appalling. There is also a lot to recognise from our own times.

Luckily, Tom Holland is a very good writer and historian and has written a superb history book, one of the best I've read. I can thoroughly recommend this, even to those who might be averse to "history". This is the opposite of dry.

At the ROI show this morning again and artist Adebanji Alade was doing a demonstration of portrait painting in the main space.

He made a great start, capturing a very good likeness. This was a "drawing" phase in thin, diluted brown oil paint, getting the proportions and large shapes down, before moving on to the darks, mid-tones and then lights. He has quite a presence and is very personable and fun to listen to. He made sure to describe the steps he did and why; it was really useful listening to him talk.

He has some work in the show this year and a great web site. This includes some video clips of him painting on the BBC.

A few financial or property bubbles around just now: Sweden has a bit of a housing bubble, Australia as well. The Economist has an article about another one: Bitcoin.

One bitcoin has jumped in value from $1,000 to over $10,000 this year, making some people very rich indeed. That's if they can sell them because it's not such a liquid market. As the article says about each Bitcoin transaction :

Each transaction has to be verified by “miners” who need a lot of computing power to do so, and a lot of energy: 275kWh for every transaction, according to Digiconomist, a website. In total, bitcoin uses as much electricity a year as Morocco, or enough to power 2.8m American households. All this costs much than processing credit-card transactions via Visa or MasterCard.

There are people who are starting to worry about whether bitcoin mining will impact "climate change" plans. As for bubbles and their end-game, they also note :

Some remember Nathan Rothschild’s remark about the secret of his wealth: “I always sold too soon.”

Bitcoin seems to have climbed to $17,000, adding over $4,000 in less than a day! It's so volatile that who would want to use it as currency? Who knows what it is now ...

The Tate Gallery has had some very good exhibitions on recently, and with more to come, I decided to become a member. My first visit as a member was to Tate Modern on a horrible grey drizzly Sunday morning for the Modigliani show. I really like this early Twentieth Century Italian artist: his angular, colourful paintings are instantly recognisable and classic "modern" art.

Right: Jeanne Hébuterne, Oil on canvas, 1919, 91.4 x 73 cm

Below: Jean Cocteau, Oil on canvas, 1916, 100.4 x 81.3 cm

Above: Portrait of a Girl, Oil paint on canvas, 1917, 806 x 597 mm

The exhibition was excellent, with a lot of paintings and some drawings. Iconic portraits and the classic nudes. One of the subjects was Jean Cocteau (see above), a lovely painting but one where Cocteau (who bought it) said :

It does not look like me, but it does look like Modigliani, which is better.

Tate Modern is cavernous, and can be drafty. An enormous and impressive space but one that they sometimes have trouble filling. So, meanwhile in the main space, they put a soft carpet down with a playground at the bottom and, as the families appear, it is soon taken over by children of all sizes, many small ones lying down and rolling from the top. Quite funny to see actually. Enough of this pompous art stuff! Thoughts I've sometimes had in this building.

The 2017 Royal Institute of Oil Painters Annual Exhibition is on just now and, as usual, has many very good paintings in it. Even one or two acrylic pieces. One of many good artists on display is Lucy McKie, a phenomenally good realist oil painter. I would encourage you to check her web site to see how amazing her stuff can be.

Her picture of the bus (below) was used on the cover of the catalogue this year.

Lucy McKie was only one of many artists and paintings worth seeing however. The show is always worth a look, and only five minutes from Trafalgar Square. I'd like to go again, but note that it ends next weekend.

Below: Lucy McKie, Old Toy Bus on Glass

Below: Adventurer

The National Gallery has a good YouTube channel, with talks about paintings, discussions about exhibitions and behind the scenes looks. A good series for the season is called Gold, and one episode looks at how the framing department works. The gallery has a lot of frames to take care of, and many are very ornate with a lot of embossed gold to them. It also has a mention for one of the largest and most ornately framed paintings the gallery has, the painting The Raising of Lazarus.

The Buried Giant

By Kazuo Ishiguro

Score: 1/5

I have wanted to read something by Ishiguro for a while and saw The Buried Giant for sale cheaply in a charity shop. This was about two weeks before the world learned that he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Unfortunately, I found this book to be terribly dull and written in a very flat and boring way. Some sort of "fable", I started to wonder if it was aimed at children, or young adults. I kept on expecting something more to happen and be explained, perhaps a deeper significance to the novel. For this reason I pushed on and forced myself to finish it, but the ending was also a big disappointment. No doubt the Booker Prize winning Remains of the Day is better and I still plan on reading that. But avoid this one.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

By John Le Carre

Score: 5/5

Another book I suddenly had an urge to read, and an author I want to read more of.

This is a real slow-burn of a book. Piece by piece, we build up a history of a cohort in the secretive world of the intelligence service. From their pre-war student lives to their war experience and then the post-war Cold War. Something is not quite right; an indication of a mole inside the organisation and the task of George Smiley is to dig the mole out. And this is what he turns himself to do: in a slow and methodical way he gathers evidence and starts to build a picture of the enemy and their accomplice inside the gates.

Le Carre has a great ear for the dialogue and patterns of speech and the characters are beautifully written. All the various code names and colour of life in the Circus alongside the 1970's colour of life in London as well. It's a rare book I start to try and postpone finishing, but I started to put the climax off as I approached the end. One of my favourite books.

Famously, Alec Guinness played George Smiley in the BBC's adaptation of the book, and it has also been re-made as a feature film recently/ I have not seen any of these but might try to. At least the Alec Guinness version, who I can picture as Smiley much more readily than Gary Oldman.

The nicely monoschromatic stairway leading down to the National Gallery's Monochrome exhibition.

I wasn't expecting too much but was pleasantly surprised, with a lot to see and like; including a Chardin, Van Eyck and Dürer. Once I'd seen the exhibition, I had a look at the Degas.

When I'm up in Scotland, I often mean to visit the Burrell Collection in Glasgow, but have never managed to get around to it yet, mainly due to the slight difficulty in getting there. Now it's closed for refurbishment until 2020.

Above: Le Foyer de l'Opera, c.1877-82 (pastel on board)

While closed however, the National Gallery in London has managed to borrow the Degas pictures and put on a free show. Degas was a very talented artist and, although usually considered alongside the Impressionists, he went his own way. Famous for his ballet dancers, he can really capture the human form and movement with a few strokes of the pen or brush, and his deep colourful style is also unmatched. Great at oil painting, perhaps even better at pastel painting.

A lovely small exhibition with a chance to see some great work.

Below: The Rehearsal, c. 1874. Oil on canvas

This painting is used to illustrate the ROI Paint Live 2017 Challenge on the Mall Galleries web site just now.

Below: Midday Sun, David Curtis

I love the way he's painted the sunlight here. Great Painting.

Paul Cézanne has always been an artist I've admired but most of his work I've seen has been his still-life and landscapes, the major part of his work. Apart from a mini-exhibition a few years ago at the Courtauld on his card-players, his paintings of people are not seen so often. The National Portrait Gallery in London has a new exhibition devoted to Cézanne Portraits that rectifies this.

Right: Hortense Fiquet in a Striped Skirt, 1877-78, Oil, 72.5 x 56 cm

The exhibition covers portraits he made throughout his life. The very early ones (pre-1870) are quite different however, and I have to admit that I really didn't like them at all. Dark and heavily painted with a palette knife, the paint was thick and spread around in large areas, almost as if by a trowel. I could see why they might be rejected from the Salon. Luckily, the earlier, uglier paintings are soon replaced by better ones.

Left: Man in a Blue Smock, 1896–97, Oil, 81.5 x 64.8 cm

Once we get into the 1870's, Cézanne finds his style, and thankfully also his brushwork. This brushwork often consists of the short, parallel and diagonal stroke we recognise from his landscapes; a style that distinguishes his art and what makes him so recognisable.

Not all are good and he struggled with figures sometimes, especially faces and expressions (sometimes very doll-like). The show is well worth a visit though. Cézanne is one of the great artists.

A blog post about the show at the NPG site.

Look to Windward

By Iain M. Banks

Score: 4/5

I read this a few weeks ago now but not managed to post about it. This was another very good Culture novel; one of the best I've read. Banks seems to get better as he wrote the series.

This book covers pain and loss of war, and the morality of revenge. All told from a very Banks viewpoint, with characters not always all they seem and technology of the "magic" variety (so high it seems like magic, per Arthur C Clarke's famous quote). A wonderful addition to the Culture universe with a beautiful and bittersweet resolution.

Goodbye to All That

By Robert Graves

Score: 4/5

An autobiography written at the age of 34 is slightly unusual, although it does not seem to stop the modern celebrity or TV star. Graves had weightier reasons however: surviving the slaughter in the trenches of the First World War.

I read his translations and rewriting of the Greek Myths a long time ago, and have also attempted to get through his White Goddess, but have never read or attempted his most famous works, the I, Claudius novels. Graves always considered himself a poet foremost, and describes his meeting and friendship with Sassoon here. He became very dispirited and somewhat bitter about the war, and who could blame him? This appalling event still casts a long shadow, and can even make me angry today. His background, class, education and whole milieu is from another age, long gone now and worth lamenting, at least in part. An interesting and original thinker and writer.

I've been up to Edinburgh for a few days recently, popping over to Glasgow as well, and a lot of time spent looking at art. Some of my favourite artists are the so-called Scottish Colourists. They were never a formal art "group" but shared a similar outlook on art in the first third of the 20th Century. Artists like Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell, Samuel John Peploe, John Duncan Fergusson and George Lesie Hunter are still well represented in Edinburgh and Glasgow galleries. There was also a recent showing of some Peploe at the Richard Green gallery in Mayfair recently.

A YouTube video of Michael Palin talking to National Gallery curator Caroline Campbell about his favourite paintings at the gallery mentioned some TV work he did on the colourists. It turns out this episode, split into four parts, is also available on YouTube. What a great resource it is :

Bygone Edinburgh, as well as bygone France.

The programme includes an appalling story about Hunter's final end, and the danger of not following safe studio practice with regards to dangerous substances like turpentine. A very sad tale.

The August Bank Holiday in the UK is traditionally wet and horrible - except the weather this time was really nice. The Saturday held out well: hot and sunny. This made the revellers at both the Notting Hill Carnival and the South West Four weekender (round my way) very happy. Most years I feel some sympathy for them: wellies required, even if the girls aren't wearing much else. Not this year though.

On Saturday mornings, I normally pop out and have a coffee, and often a croissant, somewhere in the West End before a museum or gallery visit (or even shopping on occasion). One of my favourite places for this is the Waterstones bookshop on Tottenham Court Road. It's a fairly recent arrival and I got into the habit of going for a lunchtime coffee there before my work moved to Wapping. Good bookshop and a lovely, relaxed cafe/bar downstairs (yes, even beer and wine), with great coffee (a favourite coffee is Union Bobolink).

To top it off, the people who work there are helpful, friendly and know their books and make it a pleasure to pop in and have a chat sometimes. It works to encourage the odd book purchase as well and keep the book queue a good size.

After this, I went to the RA for their Matisse show, Matisse in the Studio. I have to admit that Matisse was never a favourite of mine; I like some of his graphic work, drawings and design patterns but I was often lukewarm about him. Certainly colourful and often playful. This show did not change my mind, although a lot was more the bric-a-brac and pieces he had around him from his studio, things that might inspire. I still enjoyed a stroll around the exhibition, especially his bronze sculptures and some of his drawings. A comment in The Guardian suggests that the Matisse on show at the Bernard Jacobson Gallery (Duke Street) might be better.

On the way home, I came across an odd sight: a queue of women outside the Institute of Directors buildings on Pall Mall. Some a lot older than "girls", but all dressed in some sort of cosplay outfit, a cross between a schoolgirl and Goth. I suspect this is a Japanese Manga style or offshoot but also part of the 21st Century eternal childhood. A bit bemusing to everyone passing by!

A slightly different pastoral theme compared to the American writer Philip Roth. This is Pastoral by Frederick Cayley Robinson, painted in 1923 and hanging in the Tate. It caught my eye: a very striking painting. I took a crop of it for the banner of this blog.

Inversions

By Iain M. Banks

Score: 3/5

I've been enjoying a few Banks books this year, including a re-read of Excession, also reading The Hydrogen Sonata and Surface Detail. All three books were excellent. Inversions is hardly a Culture novel at all: a very Medieval level world with equivalent superstitions, warfare, justice system (rudimentary, including torture) and extremely basic science and medicine. Almost a standard issue murder, plot, intrigue and war waging novel from the European Middle Ages; except that there is something a bit different about the Doctor, and possibly the Bodyguard as well. Hints that they are not quite what they seem, and things that remain only hints right to the end.

I liked the book but was glad it was not much longer. Interest was held by wanting to know who the Doctor really is, and are your suspicions confirmed? I suspect this one would be a disappointment to many of Banks' Culture fans but one I'll give him a pass on.

At the National Portrait Gallery to see The Encounter exhibition (drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt), I saw the Sargent exhibition book from 2015 on sale. Looking through it, I paused on the page with his amazing portrait The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit from 1882. A beautiful painting and quite unusual in its composition for the time. The Museum of Fine Arts page is a good description of it and its reception.

.jpg)

The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, John Singer Sargent, 1882, Oil on Canvas

It reminded me a little of another painting I had seen recently.

Compare with Rupert Alexander's portrait of The Levinsons on display in the BP Portrait Award show this year. A classic style and a very Sargent feel to it. This is a picture with only four of their five daughters.

The Levinsons, Rupert Alexander, 2016, Oil on Canvas

The Encounter was really good; drawing is the absolutely fundamental base to much good painting and there are some excellent examples here. I really hate the way the NPG add a "booking fee" though. It is over 25% of the cost of my ticket!

Dead Souls

By Nikolai Gogol

Score: 4/5

You can download the ebook here.

Nikolai Gogol wrote this before 1842, and before the emancipation of the serfs by Tzar Alexander II. The souls referred to are those of the serfs, chattel of the landowners; bought, sold, mortgaged.

Paul Ivanovitch Chichikov travels around Russia trying to make money with a clever, but slightly odious, scheme he thought up. Visiting landowners, he cajoles them to part with their "dead souls", that is serfs who have died but still exist on the rolls from the last census: thus still attracting taxes. Hopefully enticing people to part with them for nothing or a minimal fee, he hopes to use these names to enable himself to buy an estate in the future, using them as some form of "collateral" for a mortgage. Yes, slightly off, perhaps not quite legal. The law can be "flexible" in Russia though, and this would, in effect, enable a cheap loan and a foot up the greasy pole.

The novel is great fun and often funny. Chichikov's a form of lovable rogue, a thinks of himself as a "gentleman" but not averse to some underhand dealings. His interactions with the various 19th Century Russians he comes across is often lively, as is the sometimes comedy interlude of life from his servants' perspective. Gogol even lets the horses and dogs have an opinion occasionally and is obviously laughing at some of the absurdity of his creation.

This version was translated by D. J. Hogarth in 1916 (according to Wikipedia) and is now in the public domain. It was a good read and the Standard EBooks version is well produced (a good project). The slight disappointment is that the novel is missing the ending, and also a little fragmentary later on. Generally, we get most of it but a shame to lose out on some of the story. We are actually lucky to have what we have: Gogol never finished it, and in fact tried to destroy it!

In hard times, beauty can seem frivolous - but take it away, and

all you're left with ...... is hard times.

I first came across Paul Madonna's book Everything is its Own Reward when I picked it up to browse in Gosh Comics, maybe six months ago. A really beautifully produced hardback book of whole page pen and ink drawings of San Francisco and surroundings. I picked it up again at the weekend, remembered looking at it before and once again loved it: so decided to buy it.

Madonna wrote and drew the series All Over Coffee in the San Francisco Chronicle for twelve years. He has a real talent for observing and drawing the urban landscape.

If you click the pictures below you go to his web site store. Click the pictures there to see a larger version.

American Pastoral

By Philip Roth

Score: 5/5

Life is just a short period of time in which you are alive

So replies Meredith "Merry" Levov to the teachers assignment that week, "What is Life?". Merry is the daughter of the Swede (so nick-named by a teacher at school) and his beautiful wife Dawn, Miss New Jersey 1949 (she hates being defined by this). In the evening, the parents laugh about their daughter's precocious intelligence but her odd unsentimentality grows in the years to come, an intellectual intensity that explodes later. America changes in the sixties and so does their daughter; and their world comes tumbling down.

Of the few fair-complexioned Jewish students in our preponderantly Jewish public high school, none possessed anything remotely like the steep-jawed insentient Viking mask of this blue-eyed blond born into our tribe as Seymour Irving Levov.

The Swede has it all and grows up in a post-war America brimming with optimism for the future; an all round athlete, good looking, ex-Marine (a drill instructor no less) but luckily misses the fighting as Japan surrenders. Laid back and comfortable in his own skin, everyone loves him. He even marries a Catholic: From Elizabeth. A shiksa. Dawn Dwyer. He'd done it. The American dream.

This novel is very funny in parts and also very moving. Much is an amazing internal struggle by Seymour Levov to understand the turn his life has taken. Roth writes an elegy almost, to an America that (sometimes literally) blew up, a Newark City that burned in riots and went down hill from there; a middle class that fled but couldn't escape the changes.

Roth beautifully evokes an old mid-20th Century "Americana", a place of growing wealth and huge aspiration. Everything is going so well, until the year 1968 and everything starts to fall apart because of Merry's cataclysmic actions. This is the power of the book; the beauty and wondrous potential so well described, colliding with the terrible fragility and reality of the world as it is. A great book and justly a Pulitzer Prize winner.

LARA, with whom I did a weekend painting course a while ago in their Vauxhall studios, are moving: to Clapham. This is where I live so I'll have an easy visit if I do anything like that again. A good move I'd say! A bit more to see and do around Clapham as well.

We found Clapham North to be a gem of a place: it boasts many coffee shops, bars and restaurants and is only a short walk away from both Clapham Picturehouse cinema and the vast green space of Clapham Common.

A comment online was stop interrupting her and let her get on with the third book!

This interview with Hilary Mantel is actually from 2015, so she's had some time since to get on with the third and final book in her great Wolf Hall trilogy. The interview is very good on the process of writing and research she has. Her favourite novel is Robert Louis Stevenson's Kidnapped, surprisingly enough; a book I read when I was at school but should revisit I think. A cracking adventure. I've been very lucky with my choice of books this year; long may that continue.

Hydrogen Sonata

By Iain M. Banks

Score: 5/5

This is Iain Banks' last Culture novel before his premature death in 2013. I've read quite a few of them now and I think this one was one of the best. I think it is my current favourite after Excession and Surface Detail.

The Hydrogen Sonata is the common name for T.C. Villabier's 26th String Specific Sonata for an Instrument Yet to Be Invented, MW 1211. The instrument invented to play it is described as :

the notoriously difficult, temporamental and tonally challenged Antagonistic Undecagonstring - or elevenstring as it was commonly known.

Yes, Banks often injects a bit of fun into his work. Having four arms, as the novel's protagonist has (by choice), seems to help play the piece. She's never managed to but is working on it.

As usual, it is full of amazing futuristic detail, alongside the moral and philosophical digressions he often mixes in. What made this book great for me was the fact that it had a good plot and fast pace, alongside a lot of often explosive and inventive action sequences. The Culture and the AI Minds might be a generally pacific and peaceful civilisation but when required they know how to deal out a bit of death, destruction and general mayhem. I think Banks seems to relish this as well.

A witty, fun and fast paced thriller, set in an amazing post-scarcity world full of wonders. And a great last addition to his work.

Some John Singer Sargent watercolours are on display at the Dulwich Picture Gallery and well worth a look. Sargent was such a great artist, and these paintings show his mastery of more than just oil painting.

Like many, he loved Venice and painted it regularly; it would have been a lot less crowded back then. As well as Venice, there are lovely paintings of friends, family and landscapes, as well as some work done as part of his stint as a war artist.

There are also a selection of photographs to accompany parts of the exhibition, some showing the great man at work or background detail to his travels. He made a good living from his portrait painting and did a lot of travelling around Europe and the Middle East, always busy recording in paint. As a result, he was very prolific, so we have a lot of work to enjoy.

Below: An unusual panorama painting of Constantinople Sargent did in 1891.

It's that time of year: a multitude of great art shows around London making for a very busy set of weekends. Some have to be visited more than once. The BP is free luckily.

The BP Portrait Award 2017 is a good as it always was, and perhaps as good as it gets. It's probably the best and most consistent annual art exhibition around, although it is highly selective so we see the best of the best ("2,580 entries by artists from 87 countries").

Right: A Russian Artist in China by Bao Han, Oil on canvas (link)

Right: Portait of Beyza by Mustafa Ozel, Oil on canvas 9link)

The above two are just two of many I might have decided to display here, but they are ones I particularly liked. For the full list, including the prize winners, see : here.

The RA Summer Exhibition rolls around in June every year and it is always a huge mix, as much "art and craft" as art sometimes. Who is to say where the dividing line is however? It includes art "installation", video pieces, architectural work and even performance art this year. And a few paintings, drawings and prints of course, the things I prefer. There's plenty I don't like but also some beautiful work as usual.

The Bill Jacklin paintings are great: a detail from one is above. Many of his pictures have a great movement and swirl of people, sometimes battling the elements and sometimes dancing or skating. The swirl of crowds in the big city. If you look closely, the individual is barely delineated, fading into the surrounding air. Fred Cuming also had a few works hanging, some of which were a bit different to the ones I've seen before. I love his atmospheric landscapes and he has a small solo show in the Keepers House, as I've reported before (I had another look yesterday).

There's always a lot to look at, although I sometimes find myself moving through the rooms more quickly than usual. It's a lottery who gets picked and perhaps I found less to like than before. I must check out Not the Royal Academy again. Unlike many "Royal" exhibitions, that one's free.

I spent last weekend at LARA, the London Atelier of Representational Art, in Vauxhall (a short bike ride from me) doing the Still Life Masterclass. It's quite different doing a solid few hours of painting rather than my usual 30 minutes here, 60 minutes there. I definitely learned a few things, including the first time using the sight-size method of drawing a scene. I also learned that standing around painting can give you backache after a while! Even though it can be a bit frustrating when you don't manage to produce something very decent at the day's end, I'm glad I did it.

The artist instructor was Lizet Dingemans. She was very good, offering advice and good humour. She painted the lovely small fish still life used in the class mails (see below). Coincidentally, I noticed I had taken a photograph of a piece she had on display at the Mall Galleries in January, as part of the Lot 5 Collective show: the Kettle painting.

oil on wood, 4x6"

I did have some trouble on occasion however. Something to be expected really.

I was far too literal in what I took with me, basing it off the "materials list" only, nothing else. This was a bit stupid because the course turned out to be very free and relaxed. I also bought a traditional wooden palette and only brought the paints in the list, including buying the Cobalt Blue, quite an expensive tube of paint (the "cheap" option being a Winsor&Newton at £20 for a small tube). With such a restricted set of paints, this also meant that the choice of painting a lemon was a poor one because I only had a Cadmium Yellow (a very orangey-yellow)! Luckily, I borrowed a more lemony-yellow, and brought my own the day after. I also created a terrible "colour study" and ended up using a white canvas for the final painting ...

But, I ended up OK and managed to pluck something half-decent from the wreckage I think. The "classic" orange, lemon and lime still life ...

Right: My LARA still life, oil, 8x10"

I painted around the white edges of my canvas in black when I got home and this made it look better. Overall, a very good weekend of art.

The Secret History

By Donna Tartt

Score: 5/5

Quite a cult book and one I've been tempted to read for years. Now I've read it, I know why it's so highly regarded. I really enjoyed it and it turned into one of those rare books you recognise as special as you read it, and one you don't want to finish.

Right from the start, you know the name of the victim and the perpetrators; the rest of the book is a slow but fascinating exposition of why this happened. As Tartt has said, this is a whydunnit not a "whodunnit". We know all the details of the crime and what led up to it half way through the book and are left with the consequences.

The novel follows a group of six students at a Vermont College through the eyes of Richard Papen, a newcomer and outsider. From California, he invents a more privileged back-story to cover his humble origins and to try and fit in with the others. They're East coast and richer. One or two are extremely well off, although there's a bit of an aura of dissolution around. Henry is the dark core of the group: tall, strong and a language savant, in love with the ancient world but cold and a bit odd. This group are "elite" in that they decide to drop almost everything except Classics, studying with one teacher only, the charismatic scholar Julian Morrow. They live and breathe in Greek and are submerged in a world very different to the modern. In fact, for much of the book, the world I felt submerged in was more F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby and the "gilded" 20's rather than the 1980's. The occasional reminders that the world we're in is actually the modern one was a jolt sometimes.

Great characters are the centre of the book and the story is driven forwards to an unexpected conclusion; you see things are starting to fall apart somewhat but never know where the pieces might end up.

I have also bought Tartt's The Goldfinch and look forward to reading it.

At a recent visit to the RA, I saw the book The New English, a history of the New English Art Club, on sale at half price and bought it. I read it before visiting the NEAC annual exhibition at the Mall Galleries at the weekend and it was a good background. The art world is often full of strange characters and competition, and also some biting criticism. The NEAC often had to contend with the same question asked every few years: is it "new", and what makes it "English"? A worthwhile read but with some great pictures of course.

And so to the 2017 exhibition. Very good as usual and a stand out painting is one others also picked out. This was a large Peter Brown painting, really capturing a very rainy street in Bath :

Above: Absolutely Chucking it Down, George Street, Bath, Peter Brown, Oil, 152x191cm

This was awarded the "The NEAC Critics'" prize for 2017. Very deservedly I think.

The LLEWELLYN ALEXANDER gallery at Waterloo is having its annual show of RA Summer Show rejects, Not the Royal Academy. Always worth a visit anytime, the show this year is full of some wonderful stuff. What gets in to the RA show is very subjective obviously: they don't always get it right.

This painting is not on their web site but I liked it so much they sent me a copy.

Tiptoe Through the Tulips, Oliver Canti, Oil pastel on board.

A really lovely painting and a snip at £1250.

I've seen a few funerals at St Patrick's Church in Wapping since my work moved here in January. One funeral had a bit of an entourage, including a horse and carriage for the coffin, but nothing was like the recent funeral for Willie Malone.

The Malone funeral was on a very hot day, so I felt some sympathy for everyone in a suit and tie and there were a lot of people around dressed up. In the café, I was told a bit of background about the deceased, being well known and referred to as "Mr Tea". A real "East End" mix of people, and there were also a couple of (what I guessed were) press photographers. In fact, a report was in the East London Advertiser, with lots of pictures. Apparently, there was a bit of "colour" in his life.

I came by it because the church is across the road from The Turk's Head, a good café/bar I often go to for a coffee at lunchtime. I took my main camera that day, planning on a walk around the sights and taking some pictures.

From the Turk's Head web site :

the original building was once famous for being the local inn where the last quart of ale was served to condemned pirates on their way from Newgate to the Execution Dock

This is the larger acrylic painting, completed following a recent Will Kemp tutorial video course (also see A Rough Venice a few days ago). This is the largest painting I have done, and should have been even larger. The course has a canvas at 24x24" but I used a 16x16" one, which seemed large enough to me at the time! I've been doing my painting in oils recently, so using acrylic again was a refreshing change.

Overall, I am happy with it even though I didn't really get to the end of the painting I think. I did up to the "glazing" part of the course but didn't do the palette knife work: a bit afraid I'd mess up something up that wasn't too bad at the time (I took a photograph of it before and after the glazinng anyway, just in case). I even debated stopping before the glazing work but decided to try and finish the course and I'm glad I did.

Below: Venice Sunset, acrylic, 16x16" - pre-glazing

Below: Venice Sunset, acrylic, 16x16" - post-glazing

After the glazing I think I petered out at the end and then stopped. I'm slightly tempted to go back to it but I think that's it; you move on. Painting a sunset, or Venice, can also be a dangerous thing; a sunset picture can always veer into a lurid, colourful monstrosity. Hopefully not here! On to the next work ...

The painting called for some strong cadmium orange. I had some Winsor and Newton but it never stood out like the orange I saw on Kemp's video. I bought some Golden brand and it was stronger and worked better. This is not to knock W&N (good paints) but does highlight colour range per brand and how important any one particular colour can be to the overall effect.

I had another colour problem with another painting, a copy of one by a well known artist. The background blue was of a certain shade, I only had ultramarine blue and didn't think anything of it. But you discover that you cannot mix the right shade at all. Sometimes you really can't get there from here mixing colours! I found an old W&N cerulean blue which worked nicely.

This is a small acrylic painting done following a recent Will Kemp tutorial video course. There's a larger main painting to come (which I've "completed") and I'll post that separately. This study is quick and rough but still presentable I think, even if not originally designed to be a fully finished "proper" painting.

Below: San Giorgio Maggiore, acrylic on board, 6x8"

There is a very textured surface. This is an acrylic coarse modelling paste mixed in with the ground colour used, and adds the rough texture you can see. This can make for a more interesting painting experience sometimes.

On my way to the RA last week, I did some art gallery window shopping in New Bond Street and saw a notice in the window of the Richard Green Gallery about an S.J. Peploe exhibition coming up. Peploe's a well known Scottish Colourist painter of the early 20th Century; an artist and a group of artists I like. The Glasgow and Edinburgh Galleries have a few but you do not get many opportunities to see more unless you do much more travelling.

A good small exhibition of some lovely paintings, particularly the still lives. If you're in the area pop in. You can also see the catalogue online.

Right:

Still Life of Pink and Red Roses in a Chinese Vase

Oil on canvas, 25x25", 1918-1922

Some were from a private collection, some for sale. The price for a larger canvas like this

was getting close to a million (pounds sterling).

Right:

Apples and Pears

Oil on canvas, 18x21.5", 1918

Station Eleven

By Emily St. John Mandel

Score: 4/5

Existence is very fragile, as is civilisation, and few think about the perils of living without running water or electricity. They are exactly the sort of thing you need to do if you're writing a book like this though. If a virulent flu virus was ever to sweep the world again, as one did in 1918, civilisation might come to crashing halt.

Emily St. John Mandel's novel tells the story of some people caught up in such a calamity, as things fall apart after a new flu epidemic kills most of the planet's inhabitants. There is enough realism here to make you face the likely effects, a horror or what it means as everything stops working and people die, but she doesn't dwell on the horror and this is not a horror story. Switching between a select few characters whose lives intersect in some way pre and post-fall, the story never becomes morbid or hopeless. Kirsten, one of the main characters, acts in a travelling theatre and orchestra, staging Shakespeare to scattered survivors living in various settlements in the American and Canadian heartland. There is no one main character but enough characterisation is done to create believable people.

When I got to the end of the book, there was some sort of "study guide": questions a teacher might ask students to think or write about. Although the book does not seem to have a "young adult" label anywhere I could see, it had that feel about it. I think I started to consider this about half way through; perhaps the lack of swearing. This was nothing I missed.

A good novel and one I enjoyed.

The RA has another "Academician in Focus", Fred Cuming. I'd never heard of him, but this means nothing: there are so many great but unknown and to-be-discovered artists in the world, dead and alive. I really like his work and made sure I had a good look before my visit to the gallery today. He's over 80 now and still going strong.

To see larger versions, and more, visit the RA site.

A few years ago, I wrote about a system of learning called Spaced Repetition and with particular reference to an application called Anki.

A useful blog post went over similar territory recently and it's worth a read. It explains the reason why this learning method is so good, including mention of the actual research behind it. We all know that to hold a piece of knowledge in your head requires you to "imprint" it; then occasionally reinforce the memory. But how often and when should this be reinforced, for the best results? This is where the research comes in handy, distilled into an app :

Noise of Time

By Julian Barnes

Score: 5/5

When you chop wood, the chips fly: that's what the builders of socialism liked to say. Yet what if you found, when you laid down your axe, you had reduced the whole timberyard to nothing but chips?

I thoroughly enjoyed this novel, the first Julian Barnes I've read. It tells the story of Dmitri Shostakovich, the famous Russian composer, in his own words, as he lives and tries to survive the calamitous 20th Century. Born before the Bolshevik Revolution, he lived his entire working life in Soviet Russia, much of it under Stalin, with all that meant.

The book is very funny in parts, but also sad and poignant. There are some beautiful descriptions of the strange life one has to lead in such a world and the contradictions he faced. And of course, the compromises made. A wonderful book about a man who knew his limitations and struggled to create his art under the most trying circumstances.

Submission

By Michel Houellebecq

Score: 3/5

Quite a timely novel, and it caused a bit of stir on release a year or so ago. In the near future (I think 2020 or so in the book), the French Presidential election run-off comes down to Marine Le Pen of the Front National and an Islamic Party. In this alternate election, both the Right and the Left in France have imploded and the Muslim Brotherhood party just pip the Socialists to the run-off. France looks to be headed to civil war and to stave off calamity, the Socialists and Islamists strike a deal, win the election and form a government. Crazy?

It's very funny in parts, and Houellebecq writes a very good, jaded French Professor, an expert in a particular 19th Century French writer. The ennui of an academic. He's apolitical and uninterested in much of what's going on, other than it distracts from chasing girls. In the end, big changes actually happen and the French establishment seem to accept it.

Maybe a bit far-fetched but Houellebecq has fun with it and the book's a quick and easy read. It's interesting reading a French perspective but also quite unsettling in the matter of fact way a societal change like this might get rationalised. On the big day, the media seems to have a bit of a blackout, and mobile communications go down. There's a hint of smoke in the distance, gun shots and one or two bodies seen; but then maybe we can get used to the new order?

For the Professor, a large pay rise is one welcome thing on the cards, but what really sets him thinking about the future is the dangling of the likelihood of an arranged wife, maybe more than one. All satire of course, and it is funny in parts, which makes up for the fact that it's only a slight "novel" and many characters are only hooks for him to hang some political and economic background..

So, finally Le Pen is crushed again and President Macron takes the crown. But as Peter Hitchens writes, what happens next time around?

His column is worth a read and very thought-provoking. Houellebecq's novel worries you in a similar way.

At the Mall Galleries for the Royal Society of Portrait Painters Annual Exhibition 2017, I saw the usual amazingly wide selection of portraits of all types and sizes. It is always very humbling seeing such a selection of beautiful art. A couple of pieces struck me in passing.

The first, Becky by Raoof Haghighi, is so detailed it is astonishing. It is not a large painting, but he even paints the small fine hairs on her face. The second is The Four of Us by Leslie Watts, an amazing pencil drawing, again highly realistic and beautifully finished.

Below: Becky, Raoof Haghighi, Acrylic, 40 x 30 cm

Below: The Four of Us, Leslie Watts, Graphite & wax, 50 x 40 cm

A few weekends ago, I happened to walk past the Cartoon Museum near the British Museum. I've often thought about visiting (when I remember it exists) and saw there was an exhibition on called Future Shock! 40 Years of 2000 AD. I have fond memories of 2000 AD, so this was a great opportunity to have a look at the place.

I just about remember buying the first issue of 2000 AD and was hooked. It came out in 1977: an annus mirabilis for science-fiction fans and small boys (Star Wars was released the same year). Saturday mornings stepped up a gear. There was another man in the museum with his children and I mentioned buying the first issue to him, and he said he had as well (they had issue number 3 on display I think).

With 2000 AD costing 8p, I also remember the shock I had getting to the counter at the big London comic book shop Dark They Were and Golden Eyed (in a much seedier St. Anne's Court) and realising I couldn't afford the comics I wanted (at all of 35p each, if I recall). The difference here was they were US imports. My grandad didn't have an extra couple of pounds on him either, if I recall, and no plastic cards in the wallet either. Those were the days, and Soho's changed a lot since then as well (never mind inflation).

For Star Wars, I remember the special trip (twice) to London's Leicester Square to see the film and being awe-struck with it, from the thunderous first shot through the big cinema sound system. Science-fiction and comics are so mainstream now but back then it was all very new. 1977 was the birth year of a massive new media industry of films, comics, TV and technology. Back then there was no internet, and only three TV channels; now we have wall to wall media saturation. In some ways, not altogether better for it.

Darkness Visible

By William Golding

Score: 2/5

From Milton's Paradise Lost:

No light; but rather darkness visible

Served only to discover sights of woe,

Regions of sorrow, doleful shades, where peace

And rest can never dwell, hope never comes

That comes to all, but torture without end

Still urges, and a fiery deluge, fed

With ever-burning sulphur unconsumed.

Golding's novel is a tale of good and evil, morality and immorality. The nameless young boy who survives the Blitz though horribly burned down one side of his face and body is given the name "Matty", and we follow his odd progress through life. There's something strange with him: he sees "ghosts" and has memorised the bible. He does not know "what he is". The second strange character is Sophy, one half of a set of twins. Her sister Toni grows up, runs away and seems to be some sort of terrorist. There also seems to be something wrong with Sophy. Not only does she see a "Sophy-thing" inside her head, she can play act an innocence and take advantage of a keen intelligence, and a female body. Matty and Sophy are unsettling protagonists and it makes for uncomfortable reading being in their heads sometimes.

I had quite a bit of trouble with Darkness Visible, sometimes losing the sense of the narrative and re-reading a section to try and pick it up. I often couldn't, especially the strange inner landscapes of Matty's or Sophy's head. The last Golding book I read was Lord of the Flies, a long time ago for a school exam and I felt I needed crib book with notes again. This might explain some of my difficulty here; or maybe I'm a bit denser than I used to be. However, the book had a power that kept me reading to the end even though I knew that I probably would not understand it.

Nobel Prize winning authors are definitely trickier to read sometimes.

A Long Way to Shiloh

By Lionel Davidson

Score: 1/5

This novel should have been great: an author I know can write absolutely stunning adventure books full of great characters and action, and a backdrop of ancient history, Jewish scriptures, archaeology and treasure hunting. Unfortunately, the book is quite lacklustre. It really must have been an off day for Davidson. The main character, an English academic and archaeologist, is also quite an unlikeable man: a drunkard and a sexist. Not an awful lot happened really, and you were in his company all the time.

Given how good the other books of his I've read were (Rose of Tibet, Kolymsky Heights and Night of Wenceslas), I won't give up on him, but would suggest people avoided this book.

John Singer Sargent's Lady Agnew of Lochnaw is a very famous and accomplished painting, now hanging in the Scottish National Gallery in Edinburgh. In this YouTube video, American artist John Howard Sanden paints a copy of it over the course of about three hours (split over two videos) :

It is fascinating watching him do this, also a little hypnotic seeing the painting come together. He explains his thought process and what he thought Sargent did at the time he painted the original in 1892. There are many art tutorial channels and videos on YouTube and this is one of the best I've seen. As Sanden says, all the great art masters copied the great works of past masters, including Sargent. I think the final result is extremely good.

The video itself seems to be from an old tape video from the The Portrait Institute in New York. Unfortunately, it might well be an illegal upload because it starts with a warning about "duplication". So the YouTube video might disappear. In some ways this would be a shame: I had never heard of Sanden, or the Institute, but now I know what a good painter and teacher he is.

Edit: Fixed spelling on Sargent's lastname.

by Bram Stoker

Score: 4/5

Dracula is a book impossible to come to without preconceptions today; it has been read, adapted and discussed so much that it has seeped into the modern imagination almost completely. I disliked almost all the film adaptations over the years, particularly the Hammer versions, and for many years these killed the character and any desire to read the book. However, a few weeks ago I found myself wanting to pick up the book for some reason and I am very glad I did : I thoroughly enjoyed it and it really is a classic.

The initial arc of the story: the eerie journey through the dark forest, wolves and strange coachman, the forbidding castle, creaking and rusting doors, superstitious peasants, all seem so familiar today. One might even groan a little inside recalling a satire like Mel Brooks' Young Frankenstein film. So much cliché; but the story soon forges on and becomes exciting. This was quite new and fresh when written all the way back at the end of the 19th Century.

This is at heart a great adventure book, with action and drama, and above all, fright. Surprisingly, given how much the story's been rehashed, it still has a huge power to shock and surprise with real horror. Some of this is due to the characters themselves; characters I actually cared for, particularly the stricken Mina Harker herself. A very good book with some great and powerful moments; and still not for any faint-hearts.

A History of Christianity

By Diarmaid MacCulloch

This is the reason there was a significant hiatus on any reading updates recently. An immense subject and a very big book is to blame!

At over a thousand pages, I picked up MacCulloch's book with some trepidation but having read his history of the Reformation a few years ago, and heard him talk many times on radio, I know how good he is, as a writer and speaker. MacCulloch's history of Christianity covers "three thousand" years because he considers the genesis of the story as starting long before the time of Herod "the Great": with the Jews, and then the Ancient Greek and Roman world. A useful starting point I think because Greek philosophy and Roman mores come to play very important roles in Christian thought and belief. Some might say, too much.

The thought and philosophy of Christians has sometimes been that of extremes, both good and bad. To many people throughout the world, it was literally a matter of eternal life or eternal damnation however, and this mattered a great deal: so much so, that people were willing to kill and be killed. In addition, theology can also hinge on some very subtle distinctions that are hard to grasp now. Be prepared for some theology then, but if you are prepared, this is fascinating and well written. MacCulloch has a dry wit and can sometimes brings a smile (or even laugh) throughout, keeping the narrative alive and interesting.

So far, always an excellent writer and historian.

You can't really argue with Michelangelo (not even Pope's do that successfully), which meant a second visit to the National Gallery for the Michelangelo & Sebastiano show.

Part of the interest here is learning more about some of the daily routine, rough competitiveness and petty jealousies of these top artists. Michelangelo was a notoriously prickly person but warmed to Sebastiano, helping him with his composition and anatomy. This seems to have been driven by his hatred of his younger rival for work, Raphael, who many considered the better overall painter. Michelangelo worked with Sebastiano as a way to win commissions from Raphael, and a form of one-upmanship. No friendly rivalry here.

There are some amazing pieces of work in the show of course, including a cast of Michelangelo's masterpiece Pieta, his Taddeo Tondo and Sebastiano's Raising of Lazarus. One of my favourites is Sebastiano's Judith (below), a smaller painting but with a real character, and beautifully painted.

Below: Judith, Sebastiano del Piombo, Oil on wood, 1510

Below: The Raising of Lazarus, Sebastiano del Piombo, Oil on Canvas, 1517-19

There's a good overview of the show and the two artists by the curator, Matthias Wivel, on YouTube. The National Gallery has a channel of its own as well, and is well worth a browse. Some great talks in front of various works.

As I stood in front of The Raising of Lazarus, I thought to myself: that's quite an amazing frame! The painting itself is very large, almost 4m high and almost 3m wide, and the frame is impressively large and solid as well :

Looking for some information on the frame,I discovered a very interesting blog all about frames by Lynn Roberts, a picture frame expert. The blog is called The Frame Blog and has a recent post about the Lazarus frame itself, covering the paintings reframing in great detail. It really is a fascinating post, accompanied by a video :

The inventory number of the Raising of Lazarus is NG1 and so was in the original core set of paintings that started the National Gallery in 1824. This was the Angerstein Collection.

I'll almost certainly return again I think.

The British Museum has a world class collection of Chinese ceramics, the Sir Percival David Collection. Even I, almost completely ignorant of this art and craft, could see how good some of the pieces are. This vase was one small item that took my interest because of its very subtle painting and glazing. This is a Vase with ‘peach-bloom’ glaze and the museum has a page about it here. Qing dynasty, 1662-1722.

This innovative glaze was technically challenging. Potters covered the vase with a layer of clear glaze, followed by a layer of copper-rich pigment, possibly blown on, and added further layers of clear glaze on top. When fired in a reducing atmosphere, this sandwiched colour developed into soft mottled red and pink with flecks of moss-green.

I took a slightly less well composed and lit photograph of it and thought I'd try doing a painting.

Below: Peach Blossom, oil, 6x8"

George W Bush, ex-President of the United States never got much good press, and even this New Yorker article on him and his new paintings has a grudging and slightly mean-spirited tone. Leaving politics, economics and war aside though, the author really likes the paintings :

The quality of the art is astonishingly high for someone who—because he “felt antsy” in retirement, he writes, after “I had been an art-agnostic all my life”—took up painting from a standing stop, four years ago, at the age of sixty-six.

I think they're pretty good as well. Paintings of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan :

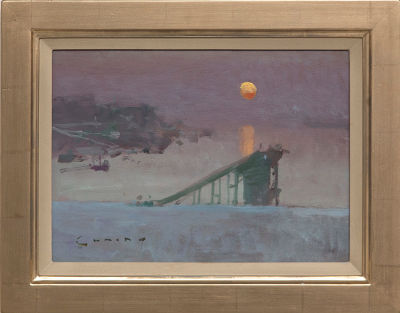

Garden in Snow, Setting Sun, Judith Gardner RBA NEAC, Oil.

As seen at the Royal Society of British Artists Exhibition 2017.

At the National Gallery for the Michelangelo & Sebastiano exhibition (which I liked), I also took some time to pop into Room 1 and see Guido Cagnacci's Repentent Magdalene, a painting that used to live in the UK but now resides in California at the Norton Simon Art Foundation.

What a beautiful painting: bright, lively and colourful. Mary Magdalene is caught at her "conversion" as her sister Martha points out the fight between an angel and a devil in the background. Martha's suggesting she ought to hear what a Rabbi she knows is saying. This is quite an unusual representation of the biblical tale (one can question its accuracy).

Below: Guido Cagnacci, The Repentant Magdalene, after 1660 (229.2 x 266.1 cm)

Below: Detail

The title of this post GVIDVS CAGNACCIVS INVENTOR is how Cagnacci signed the painting. Am unusual signature because he knew the work was outstanding. See the painting until May 21st 2017.

Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), 1972

I went to the Tate Britain Hockney show, a retrospective of his work from his early art school days to his recent works on tablet. From its first announcement last year, this was going to be a very popular show.

As I've mentioned before, I've come to like his work a lot, his newer works in particular. These are often very large, very colourful paintings, sometimes made up of multiple canvases placed side by side. I think his Yorkshire woods and hills are wonderful, and his big Grand Canyon pictures amazing. He's getting on now (almost 80) but showing no signs of slowing down. Extremely prolific, he can knock them out: and long may he do so.

Back in 2014, I suggested this might be his golden age. Looking back now, I think I was right. I also think he's still at a peak.

Below: The Road Across the Wolds, 1997, Oil.

Below:May Blossom on the Roman Road, 2009, Oil.

Below:9 Studies for the Grand Canyon, 1998, Oil.

A recent BBC documentary (BBC iPlayer) has one of his artist friends mention that Hockney was playing with the colour knob of his recently bought colour TV and cranking it right up: You can have it Fauvist if you want, he said.

It's ironic that, having spoken about his bright colours and these being such a big part of the impact many of his works have, I found that some smaller, black and white drawings he made are so powerful. These Arrival of Spring drawings are arranged in rows on the wall and I found them to be a highlight of the exhibition.

Below:Drawings of the Arrival of Spring

Below:The Arrival of Spring, Charcoal, 2013.

Below:The Arrival of Spring, Charcoal, 2013.

One could go on about him a bit now because he really has become a bit of an icon, a "national treasure" even and a lot of people love what he does. He is as articulate in words as he is in paint, and perhaps the greatest living artist. I hope he keeps going as long as he can.

A classic painting and one I've always liked, although it has been mercilessly satirised over the years (Muppet version from the RA site itself). It is easy to lampoon: prim, proper, protestant.

Right: Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930, Oil.

American Gothic is the poster-image of the Royal Academy's America after the fall exhibition. Grant Wood painted this in 1930 and he has a number of other works on display: before now, I hadn't heard of him.

Wood is the artist who most stood out for me here, with paintings like Death on the Ridge Road, The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere and Young Corn.

Right: Grant Wood, Young Corn, 1931

Edward Hopper is a more familiar artist. He has also produced some iconic American pictures and is famous for depictions of truck stops, or diners at night; his work often has an otherworldly quality, an eerieness and, I always thought, a hint of loneliness.

Below: New York Movie, Edward Hopper, 1939

There are a number of other great pictures in this exhibition and it is another very well put together show at the RA. With Revolution on at the same time, Burlington House is well worth an extended visit just now.

Slow to write this down, but I think it is worth a short report.

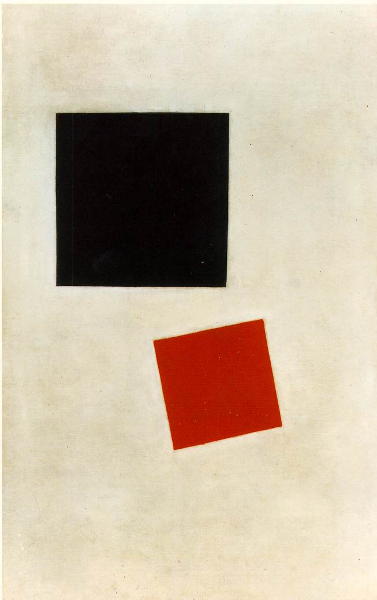

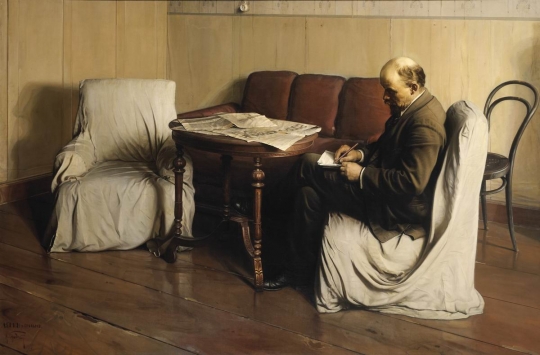

The Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932 show at the Royal Academy is very well put together and includes ceramics, print, film, photography and textiles as well as painting. It covers the style of art that first started to appear during the turmoil of the Bolshevik coup, and the early years of the revolution. Much propaganda of course, but also some real, "pure" art that passed by the watchful government eye unmolested. At least for a time.

A lot of artists here were new to me. The most famous one I knew being Kazimir Malevich, an abstract artist well known for his stark, geometric and flat coloured objects. Other unfamiliar artists I liked included Isaak Brodsky, a much more traditional painter, and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. Petrov-Vodkin had a whole room devoted to his work, the first time so much has been seen outside Russia. He started off painting religious icons and there is a vague hint of this in later work: a brightness of colour, and magical undertone. Very interesting artist.

Kasimir Malevich - Black Square and Red Square, 1915.

Isaak Brodsky – V. I. Lenin in Smolny, 1930

Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin - Petrograd Madonna, 1920

There were lots of bad times over the course of the years here: war, famine and genocide. At the end of the show is a small memorial film of some of the victims of the terror: mugshots taken before their murder or deportation to the gulag. Like everyone else, artists were not free to express themselves in the Soviet Union and the initial flowering of creativity eventually dried up, like much else.

The RA have put on an excellent exhibition however.

Wild Swans

By Jung Chang

Score: 4/5

In Wild Swans, Jung Chang tells the story of her family over the course of the 20th Century in China. This was a century of massive change and calamity in the Middle Kingdom: from "warlordism", to civil war, the cruelty and corruption of the Kuomintang and then the victory of the Communists under Mao. At first a lot of idealism as the Communists took over: stability returned, some prosperity. But over a short time things changed greatly for the worse again.

The book is a moving and fascinating account of China and the Chinese people and culture, and Ms Chang's love of the country and its history shines through, whatever the appalling hardships and cruelty she describes. Her youthful adoration of Chairman Mao slowly turns to anger and shock at the realisation of his central and personal role in the destruction of the country: its people, material and spirit.

Perhaps the saddest part of the book is about her father, a communist "true believer" in the ideals the party said it stood for. Incorruptible, and so straight and fair that he antagonised and caused many in his family (especially Chang's mother, his wife) to despair and anger Not willing to bend the knee as the party became deranged and things descended to chaos and brutality, he paid a heavy price.

In the end, once Mao was gone, things could open up a bit and Chang escaped to London and academia. Even though things are materially much better in China now, the country has not come to terms with the Mao legacy still and there are many people who still worship his memory. They are still denied a true account of their history.

If you like geology and also a bit of art, you'll like Jill McManners watercolours at the Mall Galleries. McManners is fascinated by the wild rock formations making up some parts of the Scottish Hebrides, here the Galta islands and the Shiants; wild and primeval landscapes in the Atlantic Ocean. Her own web site is good at showing off her work.

The name "Picasso" is synonymous with Modern Art. Everyone know's his name, although perhaps few will be able to name anything he did now. My younger self was a little dismissive of some "modern" art, including Picasso I'm sad to say, but now I'm older, I see things a bit differently (and now dismiss a whole new class of modern art).

I went to the National Portrait Gallery's Picasso Portraits on Saturday morning, for the second time. Although there are still many works of his I don't like, what I see now is also one of the greatest artists we've seen. Picasso was so prolific, always trying something new and always interesting.

This show displays portraiture work from his very earliest days, with his father's realist (genre) style (see above), all the way to his last works, covering abstract and cubist, naive and realistic.

To the right and below: what would people have made of these last century? Both portraits, both shockingly new and different.

Below: Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910, Oil.

Above: Woman with hat (Olga), 1935, Oil.

A lot of these works are portraits of his wives, muses, children and friends. But a few are self-portraits, the last being poignant, as he faces his mortality. A great artist.

Another great, and very prolific artist, is having his place in the sun again. David Hockney at The Tate is bound to be busy. I'm looking forward to the visit.

Roadside Picnic

By Arkady Strugatsky and Boris Strugatsky

Score : 4/5

This is a short novel by the Strugatsky brothers, written in the 1970's in the Soviet Union. The book was filmed by Andrei Tarkovsky as Stalker.

The premise is that aliens have visited Earth but no one saw them, and all that's left of their visit are a number of "zones" spread across the world, areas now contaminated with very strange and sometimes dangerous artifacts. The main character is Redrick "Red" Schuhart, a stalker, someone who goes into a zone to find and extract things to sell. It's like prospecting. It's a dangerous job because the objects might be very strange and possibly lethal: instantly or at some later time. The zone itself is full of almost supernatural elements and has effects on visitors, their minds and bodies, and also their children. Red's daughter is born with fur and referred to as the "monkey". This is all a bit strange, but compelling.

The story is almost a "hard-boiled" tale of misfits, criminals and police in a gold mine boom town but the unsettling strangeness and horror of the magical landscape at the centre makes the novel unique. Of course, Red makes a last expedition into the zone, in search of the wish-granting "golden sphere". At this point you also have a glimpse of the "meat-grinder".

A short book and a quick read, but something that will stay with you.

Not far from Tower Hill, and East of The Shard, lies the Wapping waterfront. An interesting area with a bit of history and character attached: and increasingly expensive like a lot of London. Having said that, when you are priced out of central London, expense is relative.

A lot quieter than Soho, it will take a bit of getting used to but it has its advantages. After the hustle and bustle of the West End, a quieter environment might even be one of them. Home on the bike via London Bridge and Elephant and Castle is a bit of a rat race though. Cycle routes to and from Wapping is a work in progress! A lot of regeneration has been going on down by the river for quite a while.

The Restoration of Rome

By Peter Heather

Score : 4/5

Heather's history book looks at three main characters who, wittingly or not, almost managed to restore a Western Roman Empire to existence after its dissolution in the mid-5th Century. Much of the huge amount of disruption of the 5th and 6th centuries was first caused by the eruption of the Huns into Europe, and subsequently the fighting over the spoils Attila and his tribe had accumulated. Enter the Goths.

Starting with Theoderic, King of the Ostrogoths. His high water mark covered all of Italy, Southern Gaul, Sicily and Spain, but it all disintegrated after he died in 526 AD with internecine fighting and the deaths (mostly unnatural) of successors.

Next we have Charles the Great, Charlemagne, King of the Franks and crowned Western Emperor in Rome in 800 AD, by the Bishop of Rome no less. His empire covered vast tracts of Europe (minus Spain, conquered by Islamic armies), including the Germanic heartlands over the Rhine and Northern Italy. But once again, family feud and a chronic inability to settle inheritance problems caused much to fragment a few generations after his death.

Heather then comes to the third "character", the Papacy. Initially content to play a small role in the Empire, and taking a subservient role to the Emperor even on matters of faith, the later Papacy truly found its voice. This was in large part due to the money and reformation initiated during and after Charlemagne, many changes in education and policy driven by northern Popes (the "barbarian popes" Heather mentions in the book title). Churchmen and educators were reacting aganist some serious Roman corruption in the 9th and 10th Centuries (the so-called Pornocracy).

Peter Heather doesn't shy away from using modern vernacular, or cultural references when explaining the way the world worked back then. His more laid back style might not always work but he pulls it off because he obviously knows his history and he manages to be both serious and sometimes funny. History should not be a dry discipline and this book isn't. It is a very good read because of that.

Until fairly recently, I'd never been all the way to the top floor of the V&A, where the furniture and ceramics are displayed. The top floor is much quieter than a lot of the rest of the museum but has a fascinating mix of art, craft and education.

I watched a few short videos on some new (20th Century) manufacturing techniques using PVC, Acrylic and other plastics, incuding injection moulding the Panton Chair (pictured below). An iconic design made out of molten plastic all in a single moulded piece.

The actual video is available on Vimeo.

In addition to the industrial manufacturing processes, there are many educational videos on a lot of other things e.g. the dove-tail wood joint, another short video I watched and enjoyed. The classic production and decorative processes are well represented.

The V&A has a YouTube channel with lots of great videos that seem to cover almost everything : here.

A post on Thrillist (as linked on Ann Althouse's blog) is about a bubble in the US restaurant market that might be about to pop. It mentions some problems of running a business and made me think of many bits of London, and in particular Soho.

There's a Massive Restaurant Industry Bubble, and It's About to Burst

In the restaurant world, rent always sucks. Unless you manage to play it perfectly, as a restaurant owner you're either moving into a sketchy or "emerging" neighborhood where the rent is cheap but few want to go there, or you're overpaying for an established 'hood and need to be a runaway success from day one. And even if you do manage to make it in the former type of neighborhood, your success often ends up pricing you out of the 'hood you helped revitalize.

In Miami, Michelle Bernstein's Cena by Michy helped rebirth the MiMo historic district but was forced to close this year, after the landlord attempted to triple the rent. And even Danny Meyer had to close and move Union Square Cafe in New York, which, since 1985, had served as one of America's culinary landmarks, when he couldn't rationalize paying the huge rent hike the landlord proposed.

Rent (and rates) is just one of the problems but it's a big one, and affecting a lot of people in London as well. This seems to be especially true around an area like Soho, which has been "improving" for years now, cleaned up and much shinier than it used to be. A glut of new restaurants, food and coffee places come and go regularly, and I often wonder when "peak" food will hit. The rent has exploded as well and forced a lot of closure, or relocation. There is still so much new building and renovation going on and coming online; who is affording all this?

Well, happy new year everyone.

The above painting is We Are Making a New World by Paul Nash, painted in 1918. Nash would go on to do some great paintings during the Second War as well (see Totes Meer below). A new world was surely made.